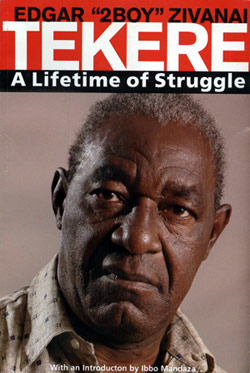

In his new book, A Lifetime of Struggle, Edgar Tekere delves into his controversial Life starting with his humble upbringing as the son of a Makoni Princess, his odssey into

New Zimbabwe.com continues with its exclusive extracts from the book which captures some of the most extra-ordinary events during the bush war that led to the country’s independence:

Last updated: 03/02/2007 01:14:20

WE guessed that the meeting at Mushandira Pamwe Hotel would probably have been infiltrated by spies, and so we decided to lie low for a while, until the matter was forgotten. This we did so successfully that I did not even know the whereabouts of Robert Mugabe. I spent my time blending in with the crowd, and “being ordinary”. I would walk to Highfield at dusk with the crowds of workers.

On the appointed day, towards the end of March 1975, someone I slightly knew approached me, and told me to wait at Kambuzuma Service Station at 7.00 that evening. I was not even aware who was organising for our escape, and during the whole period, we had no control over our destinies and movements, but were like children in the hands of others. It was a strange and dreamlike period.

Ruvimbo drove me to Kambuzuma, where I sat down on the bench to wait. Just as she drove away, another car came up, and I got into the back seat. As I got into the car, I saw a small figure climbing the security fence at the rear of the garage. It was Robert Mugabe. He was coming from the home of Abigail Kurangwa. Our driver turned out to be Grafton Rwizi Ziyenge. It was now pitch dark, and we proceeded to Cold Comfort Farm near Ruwa Rehabilitation Centre, where we were put into another car, the driver of which was Moven Mahachi, assisted by Robert Gumbo.

From there, we drove towards Mutare, on the border with

We stayed in the forest, looked after by Tangwena’s wife. It was misty with a light drizzle, and so she was able to light a fire to cook for us, without smoke being seen by our pursuers. Mbuya Tangwena called on us to join her in traditional prayers, and take snuff, as is the tradition in

All the while, the Rhodesian forces were combing the area looking for us.

The path we had to follow was pitch black, there was a heavy drizzle, and we could not see where we were going. We could not carry a torch, nor light a match, and we moved in single file, Tangwena leading the way, followed by Mugabe, myself and a young man, Nyakurita, who brought up the rear. Suddenly, I heard a loud grumble right beside us, it sounded like a lion. Chief Tangwena promptly fell down – and stayed there. When we tried to help him up, he told us to wait for a moment until he was ready. At last, he rose to his feet. “The spirits are guiding us,” he said. Most strangely, considering the loudness of the “growl” was that Mugabe did not hear a thing.

We continued to Kairezi, on the border between

We crossed during the night of 4/5 April 1975. On the morning of our arrival, there was an announcement on radio that Edson Sithole had disappeared. I remember saying to Mugabe that we would never see him again. The following day was a Sunday, and we rested and dried ourselves at a fire we lit in the abandoned huts.

We stayed with sub-chief Tagadza for some time. It was another Tangwena village consisting of quite a number of families. Chief Tangwena moved back and forth across the border, arranging for the escape of more people. He was also involved in diplomatic manoeuvres with Frelimo, the Mozambican Liberation Movement, as

It was harvest time in Tagadza, and we joined the Tagadza people working in their co-operative field.

My first disagreement with Mugabe took place then. We were discussing what we would do when we met the other recruits, and Mugabe was adamant that we should tell them that we were in the UANC, according to the Lusaka Accords. This made me extremely angry, and I said, “What a treacherous mind you have! We are here by decision of ZANU. I am not part of the UANC. You are a betrayer. I’m going to report back to those who sent us here about your betrayal!” Tangwena was with us at the time, and he managed to make peace between us, and Mugabe insisted no further. But after that I made sure that he did not meet any of the recruits when I was not there too, in case he began to talk about UANC.

As we proceeded, I made all the arrangements and took the lead, ensuring that Mugabe complied with the ZANU line. Finally, Tangwena told us that he had established contact with Frelimo. “I am giving you up to your friends, Frelimo,” he said. We walked from Tagadza to a small Frelimo camp under the command of a man called Joao (John). The camp, called Panzi, consisted of a single platoon of 15 soldiers. We were placed in the care of a young Zimbabwean from Mtoko, called Graciano (Godfrey), who had fought in the Frelimo army. Joao said to Graciano, “Here are your chefs from home, so it’s your responsibility to look after them.” Graciano became our first bodyguard, a constant presence, with his AK47 to hand. He also cooked for us, sadza with cassava leaves, which were very bitter.

The nearest town was called Vila Gouveia, where a large group of recruits had gathered, kept in holding camps by the Frelimo soldiers. When these recruits heard that we were in the area, they sent two of them to meet us. Caxton Mavhera and Nesbert Makotsi are now both dead, buried in the Manicaland Heroes’

So we walked again to join recruits in Vila Gouveia, and waited for what would happen next. The recruits were about 400 in number, channelled there by Frelimo as they crossed the border in different places in to larger and larger groups. We had to learn to take charge. There was nothing much to do than to exercise and keep fit. The new recruits were all boys, who expected to immediately be given guns and go off and fight; they wanted to go and kill all the whites! So there was quite a lot of political education to be done.

In order to relieve Frelimo of some of the burden of having to feed all of us, we went out to surrounding villasges and assisted with the harvest. In return, we were given maize and nyemba (cowpeas). We received rations from Frelimo, and also refugee aid. We called 1975 gore remadora.Madora are small edible caterpillars which are regarded as a great delicacy by the Shona.

We were moved again, this time to a more permanent location at Chimoio. Now numbering about 1000 people, we were moved in trucks to Junta, urban barracks vacated by the Portuguese. There we found about 3000 more recruits, and for the first time, we encountered females. Opah Muchinguri, Irene Zindi and Eunice Chadoka were all there.

There were also young children, some as young as six or seven years of age. Mugabe and a Mr Mashava, who had been a headmaster at Mutambara, worked together to erstablish an education department. We built schools and there were plenty of teachers among the recruits.

Mrs Mushava, who was a nurse from Mutambara hospital, became the founder of the medical department.

The commander of

There was the medical camp, which boasted a mobile operating theatre, run by Felix Muchemwa, a qualified surgeon. The school camp was run by Dzingai Mutumbuka and Fay Chung.

My favourite camp later became the site of a horrific massacre by the Rhodesian Forces. Production camp, known as Nyadzonia, after the river that flowed around ijt, was located in a horseshoe bend in the river, and I immediately thought that it was ideal for producing food, as the river could be used for irrigation. But it became a death trap, as the Rhodesians attacked from the West, at the narrow entrance, forcing our soldiers into the river, where they were either drowned or eaten by crocodiles. The livestock was bombed.

At first, Mugabe and I lived in the officers’ quarters at the Junta barracks, until Frelimo housed us in a residence in Chimoio town. We lived next door to Governor Moyana, and Jehovah, the Provincial Commander for Manica.

Eventually, the trained ZANLA fighters, including Teurai Ropa Nhongo, (nom de guerre of Joice Mujuru), heard about us and came across to Chimoio, where they decided to join us. Teurai Ropa (draw blood) had joined the liberation movement when she was in Grade Seven. She came with others from north-east

My own military training had begun in Tagadza, where we first crossed the border into

My second instructor was Joshua Misihairabwi, whose real name was Mark Dube. He taught me basic handling of explosives. Besides the individual coaching, I joined the recruits in various training camps, such as Nachingwea. I went to

Although I was a senior figure in ZANU, a commander in my own right, I had to learn how to fight, and there were many real fighters whom I looked up to. Those people I admired include Edzai Chimonyo, now a general in the Zimbabwe National Army, Gurupira, Morgan Mhaka and Chinamaropa, my teacher. Rex Nhongo and Mark Dube were among the highest ranking fighters. Morgan Mhaka taught me the humility of carrying a gun. A gun should humble you when you carry it.

Frelimo had a very sophisticated intelligence network, and one day Jehovah showed me letters they had intercepted, informing the Rhodesian authorities about us, our activities and whereabouts. Two spies, Dorothy Mukombe and her boyfriend, David Mwamuka, had been writing them, and Frelimo had someone at the Mutare Post Office who would intercept the letters and return them to

“Your home girl,” Jehovah said, “This is what she is.” But they did not arrest her, because she was providing them, with useful information. This caused Frelimo to be very concerned about the safety of Mugabe and myself. Not long after Frelimo told us about them, the pair was involved in a serious road accident in Vila Manica, and Jehovah had the injured pair transported to the border with

A Lifetime of Struggle by Edgar Tekere is published by Sapes Books in

To order any of the books, E-mail: ibbo@sapes.org.zw or Call +263-4-252961/5 OR +263-4-704921, Fax: +263-4-252964

--

Posted By "The Radical Mindset!" to "TEKERE TALKS!" on 3/02/2007 08:09:00 AM

No comments:

Post a Comment