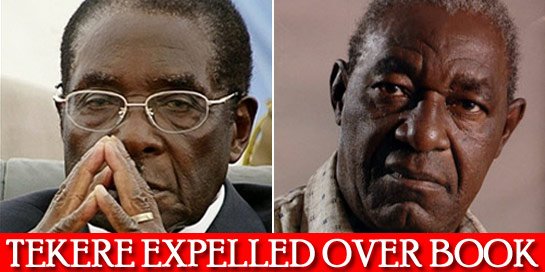

| By Geoff Nyarota I have just finished reading Edgar Zivanai Tekere's "best-seller", A Lifetime of Struggle. What I have crafted here is by no means a review of the book. I don't believe that it would be entirely appropriate for me to write one. I would certainly be accused of sinister motivation if I reviewed a book that was published a few months after my own title Against the Grain, Memoirs of a Zimbabwean Newsman. On ethnic grounds, I am most reluctant to write a review of A Lifetime of Struggle. I am of the Makoni clan in the eastern districts of Zimbabwe. Tekere's mother was, in the words of her illustrious son, a Makoni princess, a muzvare, as the daughters of our clan are proudly called. It is with a very heart that I find myself in a professional situation where I have no option but to discharge, as Tekere's sekuru or uncle, the onerous task of ventilating very pertinent issues pertaining to some claims of mysterious income that he makes. I believe I do this in both the public and the national interest. Tekere's claims of multiple funding by well-wishers and benefactors during periods of hardship and adversity is so shrouded in mystery that I feel a strong urge to unravel the puzzle. The fact that, as an investigative journalist, my stock-in-trade is to unravel mysteries augments my misfortune in this case. After going through my muzukuru's most sensational revelations I decided I could not stand by and watch while he makes certain preposterous claims that have the potential to even undermine the credibility of the entire clan of his sekurus. I, therefore, write with profound apologies to my muzukuru in an effort to set records straight from my vantage point on the periphery of some of the events that Tekere delves into. I had the honour to meet Tekere at the time of Zimbabwe's independence soon after he returned from his eventful sojourn in the Republic Mozambique from where the Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army (Zanla) waged its campaign of insurgency against the Rhodesian Front government of rebel leader, Ian Smith. I had the honour to accompany, along with Tekere, the late Chief Rekayi Tangwena when he travelled back to Nyafaru, up in the misty mountains of Nyanga, to meet his Tangwena people after an absence of five years, while participating in the liberation struggle. I drove Tangwena from Harare down to Nyanga in a Herald Mazda 323. He transferred into Tekere's majestic Jaguar XJ6 at Troutbeck Inn while I drove behind as we negotiated the steep and twisting road for the rest of the journey to Nyafaru. This was momentous and extremely happy occasion for both the Tangwena people and their visitors, especially Tekere. As Editor-in-Chief of The Daily News I visited Mutare and spent an afternoon with Tekere in his home in the suburb of Greenside in 2002. This was at a time when many had dismissed him as a political spent force - and worse. He fell short of restoring my faith in him as the firebrand politician I had met in Nyanga 12 years earlier. I was, however, impressed by his generally humble demeanour and by his very modest existence. He spoke of the hardship he was undergoing, which was self-evident, both from his appearance and from his disposition. There was absolutely nothing about Tekere that day to suggest it and I spent the afternoon blissfully unaware that I was in the company of a multi-millionaire. He spoke so passionately and so convincingly about penury and the hardship of his existence I even made a small donation myself. Millionaires were rare in Zimbabwe those days. This was of course before the period when even beggars on the street often became millionaires, thanks to runaway inflation. In his own printed and published words Tekere says of one of Zimbabwe's early indigenous millionaires, the eccentric tycoon, Roger Boka, now late, that he received from him, starting in 1988, "monthly cash payments, none amounting to less than Z$800,000.00, which was a goodly sum in those days". In 1992 fellow journalist, Tonic Sakaike, now also late, and I registered a publishing company as the first step towards the launch of a newspaper. We then canvassed the business community for potential investors in our newspaper project. Among the entrepreneurs we approached was the same Boka, who showed interest in our project but said the best he could do was make a donation. He signed a cheque for the then princely sum of $2 000.00 and handed it over to our project, much to our genuine delight. We thanked Boka profusely for such rare generosity. Little did we know that four years earlier Boka had routinely deposited cheques amounting to $800 000.00 every month into the account of Tekere, starting soon after the latter was dismissed from Zanu-PF for his principled stand against corruption. Tekere speaks fondly of another sponsor, one Abdulatief Parker, a Cape Town businessman who settled in Harare, and with whom the politician says he struck a relationship. "At one time Laatief (sic) opened an account in my name at a local bank, into which he deposited Z$500,000.00 every month for a period of three years," Tekere says. From this benefactor alone Tekere received a cool $18 million, at least. Then there was Jonathan Kadzura. The managing director of Rural Industrial Development (Pvt) Ltd., trading as Pamberi Marketing, Kadzura, was the first person to be prosecuted for corruption following the exposure of the Willowgate Scandal by The Chronicle. He pleaded guilty to selling four Toyota Cressidas for figures far beyond the controlled price. His source of vehicles was the late senior Manicaland politician and government minister, Maurice Nyagumbo, who committed suicide as a result of the exposure of his involvement in the scandal by The Chronicle and subsequent humiliation by the Sandura Commission. Kadzura told Mutare magistrate Philip Drazdik that Pamberi Marketing was experiencing serious cash-flow problems at the time when he sold the vehicles at grossly inflated prices. Drazdik convicted Kadzura, nevertheless. Now Tekere has the temerity to cause to be recorded for posterity with regard to the same Kadzura that, "between 1986 and 1987 he would pay Z$1,200,000.00 into my bank account every month". That's another cool $28 800 000.00 paid into the Tekere account between the provident years of 1986 and 1989. I am not making up these amounts, merely adding them up. After Drazdik found Kadzura guilty he fined him a total of $9 500, apart from the $75 000.00 he was ordered to refund to those he had over-charged on vehicles. This certainly did not leave Kadzura with much spare cash to donate to any charity. If my assessment is wrong Kadzura can always vindicate both Tekere and himself by explaining for the benefit of the public from where he obtained the millions he allegedly deposited in Tekere's account every month. In 1988, at the height of the Willowgate Scandal the factory price of a new Toyota Cressida was $27 657.00. For the amount of $1,2 million, which Kadzura dutifully and mysteriously deposited into his bank account, Tekere could have purchased 43 brand new Toyota Cressidas every month. Kadzura was convicted of making an illegal profit of $75 000.00 on four Cressidas, which he was asked to refund. The salary of a government minister at the time was a total of $24 000.00 a year. Apart from the obvious ridiculousness of Tekere's claim an obvious question arises. Assuming Pamberi Marketing, despite the cash flow problems encountered, was raking in so much in profits, why would Kadzura be so extremely generous as to pay $1,2 million to Tekere every month? For the record Tekere says Mutare businessmen, Enoch and Farai Musabaeka, who are father and son, also made unspecified but regular deposits into his account. So did politician Ephraim Masawi. Apparently he still does from time to time. Retired General Solomon Tapfumaneyi Mujuru, who is now linked to Tekere in the current Zanu-PF succession battles, was another benefactor, making deposits from time to time into the account. The retired soldier is the husband of Vice President Joice Mujuru, who aspires to be President of Zimbabwe. The line-up of depositors into the Tekere account reads like a "Who-is-who?" of Zimbabwe's political and corporate establishments. Reserve Bank governor, Gideon Gono apparently made a donation of $500 000.00 but his contribution was made at a time when many citizens now carried that kind of money in their pocket. Perplexingly, Tekere continued through the years to accept, possibly after much solicitation, further bounty from his benefactors. With all these millions in his bank account, Tekere continued to pose or to portray himself as destitute, thus attracting even more astoundingly generous donations. Astute observers would characterize such conduct as deceitful or outright fraudulent. A revelation that is glaring by its absence from Tekere's text is what happened to this vast largesse. Did he spend it? Did he invest it? Or did he, like a later-day Robin Hood, steal the wealth of the corrupt to redistribute it among the impoverished masses? A possible explanation is that the funds could have been channeled into funding the activities of his political party, the Zimbabwe Unity Movement. But in A Lifetime of Struggle Tekere is brutally candid in describing all facets of his eventful life and would certainly have said so, had these funds been donations to ZUM. In any case, ZUM would have easily attracted its own funding, not that there is anything to show now for the fact that any huge sums of money ever found their way into the coffers of that short-lived party. Tekere will probably try to wriggle out of these huge sums by suggesting that he converted all figures to values at the time of writing. But why would he do that? If this was indeed the case, then Tekere still has to explain why he cited unconverted donations of $2 000.00 and $3 000.00, alongside the breathtaking contributions made by Latief, Kadzura and Boka. Tekere does not make this explanation in his text and, in any case, normal practice would be to cite the 1988 value (with the 2006 value in brackets). "When I was sacked from the Party, his concern mounted, and I would find that my rates had been paid, in credit. I would receive monthly cash payments, none amounting to less than Z$800,000.00, which was a goodly sum in those days." These are the unequivocal words of Tekere. Failure by Tekere to provide satisfactory or convincing answers to all these burning questions will merely serve to endorse a growing perception that he has an idiosyncratic relationship with the truth. This trait has so far escaped media scrutiny only because Zimbabwe's journalists have a weakness of their own. They tend to hunt in packs like wolves, with little latitude in their professional conduct for independence of thought or enterprise. As of now, Tekere is the flavour of the month in our section of the media and he can get away with murder, as long as he is seen to undermine the perceived common enemy of the people of Zimbabwe, Robert Mugabe. Meanwhile, it is a cruel paradox that while, with cavalier disdain, he speaks ill of Nyagumbo throughout his book, Tekere apparently owes his very existence to Kadzura, who owes his prosperity to Nyagumbo, who unfortunately is not available to defend himself. One is left wondering, however, who else in Zanu-PF has raked in millions in cash and kind from Zimbabwe's business and farming communities, both white and black, since independence in circumstances similar to those described at length by Tekere. He certainly could not have been the only one to exploit his political position for grotesque self enrichment, which included donations of houses and powerful Jaguars. At one point he owned three of the luxury sedans, including two donated to him by well-wishers in one week. Send your comments to: letters@thezimbabwetimes.com This email address is being protected from spam bots, you need Javascript enabled to view it | |

| Last Updated ( Monday, 05 March 2007 ) |

Inbox full of unwanted email? Get leading protection and 1GB storage with All New Yahoo! Mail.

No comments:

Post a Comment