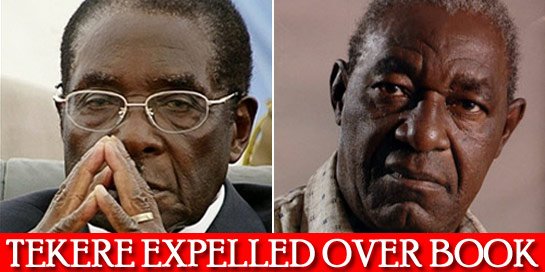

EDGAR TEKERE: THE BOOK THEY DON'T WANT YOU TO READ

Mugabe's women, and the ZAPU split

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

• The people who saved me from poverty

• Masawi threatened over Tekere book

• Tekere unfazed by Zanu PF expulsion threats

• Hysterical reaction to Tekere belies fear

• Book shop won't sell Tekere book

• Tekere absolves Mugabe of Tongogara's killing

• 'We produced a creature that destroyed this country' - Nkala

• Tekere says Mugabe 'insecure' in new book

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

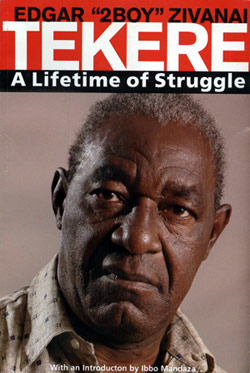

In his new book, A Lifetime of Struggle, Edgar Tekere delves into his controversial Life starting with his humble upbringing as the son of a Makoni Princess, his odssey into Mozambique at the side of Robert Mugabe, and his rise to prominence within the liberation movement of Zimbabwe.

New Zimbabwe.com continues with its exclusive extracts from the book which captures some of the most extra-ordinary events during the bush war that led to the country’s independence:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Last updated: 02/27/2007 03:06:16

FROM 1953 to 1958, the Southern Rhodesian government of Garfield Todd attempted to introduce liberal reforms to increase educational rights for the black majority but Todd was forced from power when he attempted to expand the number of blacks eligible to vote from 2% to 16%. Taking their cue from the liberal Todd, the early national movements (including the Southern Rhodesia African National Congress led by Rev Thompson Samkange, the British African Voice Association, led by Benjamin Burombo and the Reformed Industrial and Commercial Workers’ Union, led by Charles Mzingeli), accepted the reality of settler colonial rule, but opposed racial discrimination within the system.

The governments that followed Todd’s became increasingly repressive, introducing laws such as the Law and Order (Maintenance) Act of 1960 and the Emergency Powers Act which restricted the rights of the black African majority. Increasing repression, instead of cowing the people, radicalised subsequent political formations.

In 1958, discussion in our party, the ANC, focused on the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland were opposed to the Federation, as they saw that all the resources were concentrated in Southern Rhodesia, which used the other two countries merely as sources of revenue, mainly copper and cheap labour.

In Nyasaland (as Malawi was then known), the Nyasaland African National Congress was led by Henry Chipembere, Dunduza Chisiza, Orton Chirwa and others. Hastings Banda was then in Britain, and had established contact with Dr Kwame Nkrumah. The ANC asked him to return and take over the leadership. On his way back to Nyasaland, Banda travelled via Salisbury, where he was hosted by George Nyandoro in his home in Highfield Township. He spoke at Cyril Jennings Hall in the same Township, and my car was used to drive Dr Banda.

By the time Banda arrived home, Nyasaland was aflame. The ANC presented him with a broom upon his welcome at Chileka Airport “with which to sweep away the stupid Federation.” The fervour in Nyasaland also swept us up, and we joined the fight against Federation.

In Northern Rhodesia (Zambia), the ANC leader of the time, Harry Kumbula, was not as strong a personality as Banda, and thus Kenneth Kaunda and others broke away from the ANC to form the United National Independence Party (UNIP).

In 1960, the National Democratic Party was formed, since the ANC was banned in February 1959. Its constitution was written from prison by Edson Sithole. Michael Mawema was elected leader. Other leaders included Leopold Takawira, Enos Nkala, Moton Malianga and Jason Z Moyo. That was when I first met Sabina Mugabe. Robert Mugabe had not yet returned from Ghana where he was a teacher.

There were many colourful characters in the Party: Paul Mushonga was a businessman who gave most of his income to the party. James Chiweshe was another businessman, proud and jocular. Peter Mutandwa was the organising secretary of the Party, and a very religious man. Mutandwa was a diabetic, and thus whenever he was arrested he had to be accommodated in Class 2 cells, meant for persons of mixed race, and was the first African to qualify for membership of the Institute of Chartered Secretaries.

The National Democratic Party (NDP) demanded majority rule, universal adult suffrage, and impendence from Britain. For the first time, we had a clear programme, but we relied on Constitutional conferences with Britain as the principal means for attaining independence.

At first the NDP drew its support from the urban population, and was slower to gain support in the rural areas. Rural people thought our demands were too radical and did not see how we could achieve them. The ANC had been more of a pressure group than a political party, concentrating mainly on land issues.

My own position was that of secretary of the Salisbury District Council. The chair was Stanley Parirewa, and the publicity secretary was Noel Mukono, a highly qualified journalist who worked for Drum Magazine and who subsequently joined forces with Ndabaningi Sithole, went into exile through Malawi, and became part of the Dare in Lusaka in the 1960s.

In February 1961, a conference to review Southern Rhodesia’s Constitution opened in Salisbury with British Commonwealth Secretary, Mr Duncan Sandys, as chair. The conference agreed on the removal of reservations in return for a Declaration of Rights and appointment of a Constitutional Council. Parliament was to be enlarged from 30 to 45 members, and Africans were to be given representation through a ‘B’ Roll. Joshua Nkomo, with Herbert Chitepo as legal adviser, attended the conference, and accepted the proposed revisions. In those early days, Chitepo was still something of a “liberal,” and only later was to see the point of fighting against the compromise of fifteen seats in parliament. Initially, he saw the 15 seats as a “tremendous achievement,” as did Nkomo.

This we rejected, and organised our own referendum, campaigning for a No vote against the 1961 Constitutional Proposals. Widespread civil disobedience ensued. We were critical of Joshua Nkomo’s leadership, on the grounds that he travelled too much and did not consult the Party.

Meanwhile, Robert Mugabe had returned to the country from Ghana. It was suggested that Mugabe be incorporated into the leadership, but there was a problem because he was not married. George Silundika and Moton Malianga approached a young lady called Abigail Kurangwa, who agreed to marry Mugabe, and eventually fell in love with him. Mugabe appeared to reciprocate, and his family liked Abigail, so all seemed to be proceeding smoothly. But in Ghana, Mugabe had had an affair with a Ghanaian woman named Sally. When Sally heard about Mugabe’s impending marriage to Abigail, she hastened to Southern Rhodesia and they were quickly married, while Abigail was sidelined.

Sally and I never became friends, and I never liked her. But I acknowledge that my ill feeling towards her was coloured by the way of poor Abigail had been used.

The NDP did not last long. We rejected the leadership of Joshua Nkomo, and tabled this at a Party Congress in Bulawayo in 1961. I was asked by the Salisbury District Council to table the motion. It was countered by none other than Mugabe, and this was the first of many confrontations between us.

Contrary to common perceptions, Robert Mugabe tended to defer to his leaders, right to the end. This was to happen again in the case of the sacking of Ndabaningi Sithole as leader of ZANU, whilst we were in detention at Kwekwe Prison in mid-1974.

We lost the motion in Bulawayo, and were under threat from Nkomo’s supporters. In the evening after the Congress, people with knives came looking for us, and we feared for our lives. It had been difficult even to leave the McDonald Hall where the Congress took place, but fortunately for us there were riots that night in Bulawayo, and we managed to slip away and go into hiding.

Some of the statements I made got me into further trouble. On a visit to a Tribal Trust Land (poor land reserved for blacks in Rhodesia), Mubaira Mhondoro, I stated that nothing would end colonial rule but outright war. This earned me an indefinite ban from the Tribal Trust Lands.

In the Salisbury Township of Mufakose, I earned myself another banning, by saying: “My father is a priest in a church. In this church are the people who came here with the Bible in one hand and guns in the other, and who vowed to use the guns if the Bible did not work. The only way is to fight them back with guns of steel!”

In December 1961, the NDP was banned. A week later, ZAPU (Zimbabwe African People’s Union) was formed. The formation of the new party took place thus: We sat in Nkomo’s house and discussed the new name for the party. We proposed the name ZANU (Zimbabwe African National Union), and Mugabe countered this with ZAPU, as he thought ZAPU had a better ring to it. The meeting agreed on ZANU, but at a press conference called to announce the new party, Mugabe unilaterally changed the name to ZAPU.

But there was no change of structure, merely a changing of letterhead. I continued my work as secretary of the Salisbury District Council. Early in 1962, my employer, Mobil Oil, transferred me to Bulawayo, where I worked for three months until I was moved again to Gweru.

In Gweru I met up with Kenneth Manyonda, a senior official at the African Trade Union Congress (ATUC), a breakaway from the union led by Reuben Jamela. In Harare, Nkomo was urging the leadership to go to Dar es Salaam and form a national government in exile. This made no sense to me, and neither did it to Julius Nyerere, but Nkomo lied to his colleagues that Nyerere had invited them to Tanzania to form a government in exile.

Sally Mugabe had a police case against her, and jumped bail. She and Robert Mugabe escaped through Botswana to Dar es Salaam. They were joined by the entire leadership. Nyerere told Nkomo to return to Rhodesia, which he eventually did, and immediately announced the banning of the anti-Nkomo group from the top leadership, led by Ndabaningi Sithole and including Mugabe and Enos Nkala. When the three arrived back from Tanzania, consultations began the formation of ZANU – The Zimbabwe African National Union. Thus it was that Nkomo was instrumental in the formation of ZANU – ironic indeed.

Ndabaningi Sithole had initially been a supporter of Nkomo, as he too, did not want to launch an armed insurrection. But after Nkomo’s action, he decided to join up with ZANU. Likewise, Mugabe would have remained with Nkomo were it not for his drastic decision to ban the top leadership of ZAPU. Besides, Nkomo had been a good leader in the early days when he worked with the Railway Workers’ Union and then as a social worker, and he had the ability to mobilise the workers.

Throughout the history of Zimbabwean nationalist politics, it has been a tradition that a person from a minority ethnic group is brought into the top leadership of the party in power. Ethnicity was a significant factor in Zimbabwean politics, which can be seen in the way I am always associated with Manicaland, where I happened by accident to be born, and yet I had spent my whole political life in Salisbury and Gweru. It was only later, after independence, that I came to be elected – in absentia – to represent Manicaland.

The formation of ZANU took a long time to organise – from October 1962 to August 1963. This was because we had to seek grassroots support at provincial level, and Salisbury District Council was often accused of behaving like the national leadership, of being the “troublemakers.” Right from the beginning, I was considered a radical. Amidst the discussions, it was formally announced in December 1962 that Nyasaland would be allowed to secede from the Federation. This decision was bitterly attacked by the Prime Minister of Southern Rhodesia, Roy Welensky.

On 8 August 1963, the formation of ZANU was formally announced – from Enos Nkala’s house in Highfield Township. The constitution of ZANU announced that Zimbabwe was, “An African country in the context of the African continent in various stages of the relentless process of overthrowing the yoke of colonialism, imperialism and settlerism.” Independent Zimbabwe, it said, had to have institutions that respected the will of the African people, who formed 96 percent of the population. ZANU resolved to confront the enemy by a “positive programme that can only result in bringing about equal opportunity and full citizenship to everyone, regardless of the colour of one’s skin, religion or sex.”

On the same day, Joshua Nkomo announced the formation of the People’s Caretaker Council (PCC), as a holding mechanism for ZAPU. There was a massive launching ceremony for the PCC at Cold Comfort Farm, Guy Clutton-Brock’s co-operative on the outskirts of Harare.

From Cold Comfort Farm, James Chikerema led crowds into Highfield, the township where allm the political activists lived in those days, and they attacked the houses of Robert Mugabe, Leopold Takawira, Enos Nkala, and beat up people on the streets. Highfield became a battleground.

Because of the fighting, we established a ZANU structure in Gweru. Rev Mawaro was chair, I was the vice chair, and Kenneth Manyonda was secretary. Joh Mutambu was in charge of Youth Affairs, William Takavarasha was the organising secretary, and Shangwa Muzenda was a member of the Council. Later, Rev Mawaro weas moved away from the area and I took over the position of chair. The Gweru District Council in fact served the whole Midlands Province, and even parts of Masvingo.

We agreed that we needed to be advised by mature minds, and so we created a council of elders who were to guide the elected executives, and rebuke us if we did wrong. (I am a firm believer in the idea of a Senate, and I had always advised Mugabe that he should create one). The council of elders included Mrs Chigwenere (mother of Ignatius Chigwendere), among others.

By temperament, I was more inclined towards the Youth Wing of the Party. The Youth Wing went to Masvingo to mobilise support for the Party in that town. In effect, we were fighting a war with ZAPU and, as ZANU was unable to operate in either Harare or Bulawayo, the Gweru structure was fighting for the whole Party. We would dispatch teams to the other cities, particularly at weekends, to fight battles. ZAPU would go into hiding when they heard we were coming.

I am very proud of the work I did in Gweru, for if it were not for I and my team in the Midlands, ZANU would have died then. Because of the situation in Harare, our first rally was held in Gweru, in Mutapa Hall, Mutapa Township, and it was a resounding success. Three times the capacity of the hall turned out, and the crowd gave heart to the national leadership.

Thus, it was natural that the Party Congress of 21-23 May 1964 should also take place in Gweru. Ndabaningi Sithole stayed at my house in Mkoba and campaigned vigorously to be elected President. Another group campaigned for Robert Mugabe, but Mugabe himself did not take part in the lobbying. The Congress duly elected Ndabaningi Sithole President, Leopold Takawira Vice President, Robert Mugabe Secretary General, Herbert Chitepo National Chairperson, and Edgar Tekere Deputy Secretary for Youth. For the first time, the Party reflected what we wanted to do – take over the government of the country. This had never been clearly articulated until that Congress. We also resolved not to rely on foreign troops. We would fight our own battles and, “no foreign blood shall be spilled on Zimbabwean soil in the process of liberating Zimbabwean soil.”

The Reverand Ndabaningi Sithole, President of ZANU, was a great teacher, who was able to use his abilities as a preacher to articulate the precepts of ZANU. It was he who first determined that ZANU should fight, openly confront the colonial power, and no other person could have done this better than he.

In accordance with this resolution, then, we had received orders to go on and form an army in the name of ZANU. Rev Sithole assumed an additional role -- that of Commander of the new armed forces. This decision was upheld by both the leadership and the delegates at the Congress. Now we had to find out how to form an army.

A Lifetime of Struggle by Edgar Tekere is published by Sapes Books in Harare. The book was edited by Ibbo Mandaza. Also in the series is The Story of My Life by Joshua Nkomo, also published by Sapes.

To order any of the books, E-mail: ibbo@sapes.org.zw or Call +263-4-252961/5 OR +263-4-704921, Fax: +263-4-252964

No comments:

Post a Comment