And so the armed struggle began...

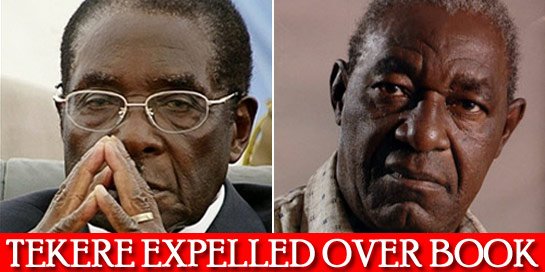

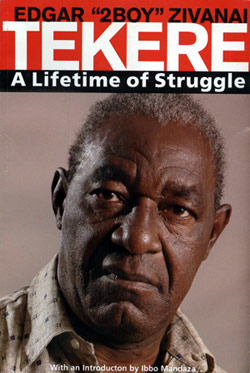

In his new book, A Lifetime of Struggle, Edgar Tekere delves into his controversial Life starting with his humble upbringing as the son of a Makoni Princess, his odssey into Mozambique at the side of Robert Mugabe, and his rise to prominence within the liberation movement of Zimbabwe.

New Zimbabwe.com continues with its exclusive extracts from the book which captures some of the most extra-ordinary events during the bush war that led to the country’s independence:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Last updated: 02/28/2007 04:03:59

ZANU was banned in August 1964, soon after the Congress of May of that year, in which the Armed Struggle was launched, but this time operations were already underway, led by William Ndangana. Operations began in the towns of Melsetter, Nyanyadzi and Mvuma in central and eastern Zimbabwe.

On 4 July 1964 Ndangana set up a roadblock and, with Victor Mlambo, James Dhlamini and Master Tresha, killed a white man of Afrikaans descent called Petros Oberholtzer in the Chimanimani farming area of eastern Zimbabwe. Ndananga and his men came to be known as the ‘Crocodile Gang’.

After this act, Mlambo and Dhlamini crossed the border into Mozambique, but the police there captured them and brought them back to Southern Rhodesia, where they were tried and hanged at Salisbury Central Prison. Ndananga himself was smuggled into Malawi. Master Tresha was also captured, but sentenced to life imprisonment as he was too young to suffer the death penalty.

After the killing of Petros Oberholtzer I had a brief brush with the police. Although I was not then operational, I held the post of Deputy Secretary for Youth -- and youth are considered the lifeblood of any war effort. I happened to be in the Chipinge area (I had been fired from my Gweru job because of my political activism), when I was arrested and locked up at Nyanyadzi Police Camp. The police suspected that I was part of the ‘Crocodile Gang’. From Nyanyadzi I was transferred to Harare Central Police Station, where I was interrogated by the Special Branch. They were tryhing to convict me of the murder of Petros Oberholtzer.

Eventually, as they were unable to build a case against me, I was released.

After the banning of ZANU in 1964, the Rhodesian security forces began rounding up all Party members. For a while I remained free, in hiding in a run-down neighbourhood of Salisbury known as Kopje. In September, the trial of Ndabaningi Sithole took place, and I was assigned to look after Herbert Chitepo, who had flown in from Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, to defend Sithole. Chitepo was booked into the Jameson Hotel, but I, who drove a small Morris Minor 1000 at that time, would pick him up and take him elsewhere in case he was kidnapped by the Rhodesians. As soon as the trial was over, I rushed him to the airport and he was immediately on his way.

I was caught again by the police in central Salisbury, along what is now Julius Nyerere Way. Since I was not handcuffed I managed to sprint through the busy traffic and disappear for a few more days, but the next was closing in.

A few days after this incident, I was run to ground at my parents’ home at St Mary’s, near Salisbury, on 16 October of that year. I was taken to Salisbury Central Police Station. There, I met Abisha Mudzingwa, another young ZANU man.

We were then transported by road to Gwelo (Gweru) Prison, where we joined Joshua Nkomo, Josiah Chinamano, Daniel Madzimbamuto and others from the ZAPU group. Daniel Madzimbamuto wanted to kill us, accusing us of the murder of his brother, who had been killed during the in-fighting between ZANU and ZAPU. When he was killed, I and my group had been descending on other towns from Gweru to fight with ZAPU members. Nkomo took us into his cell for our protection.

During the course of that year, 1964, Nkomo challenged the detention order and won the case. But instead of releasing us, we were issued with Restriction Orders.

The two groups, ZANU and ZAPU, were divided between two different holding centres, Gonakudzingwa for ZAPU members and Wha Wha for ZANU. So, Mudzingwa and I were transported to Wha Wha.

At Wha Wha were Basoppo-Moyo, Simon Muzenda, Crispen Mandizvidza, Morton Malianga, Edson Sithole, and Amos Kombo, among others.

The camps were unlike conventional prisons: they had no walls, no bars, but were located right in the bush. We knew that anyone who tried to walk away would not survive the journey. We named the place ‘Snake Park’ (after a tourist attraction in Salisbury) because of the number of snakes infesting the camp.

Barracks were provided for the restrictees to sleep in, but those who required more privacy were allowed to build their own thatch-roofed huts. Edson Sithole and I built one for ourselves. We formed a committee to manage our affairs, and called it the ‘Village Committee’. Our spokesperson was Crispen Mandizvidza. The police reservists would come once a week to make sure all was in order, and to bring our rations.

Not long after we arrived, Robert Mugabe, Leopold Takawira and Eddison Zvobgo joined us from Salisbury Prison, making up the entire complement of the ZANU leadership.

Christian Care sent us books and arranged for us to study. Edson Sithole was studying Law.

Meanwhile, in 1964, Ian Smith of the Rhodesian Front had been elected as Prime Minister of Rhodesia. Smith was famous for pronouncing that blacks would not achieve equality, “not in a thousand years.” The British, who were committed to a gradual process of slowly preparing blacks for independence – too slowly for us – were worried by this development, and on 1 March 1965, I, Leopold Takawira and others were taken to New Sarum air base near Salisbury for discussions with Arthur Bottomley, British Foreign and Commonwealth Secretary, and Lord Gardner. These were not helpful, and we did not even listen to their proposals.

On 15 June 1965 we were served with new orders and were transferred to Sikombela Restriction Area in the district of Gokwe, in Midlands Province.

Harold Wilson came to Salisbury, and I was part of the delegation sent to discuss a looming Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) by Smith. Wilson told us that if Smith did declare a UDI, we should not expect the British to intervene against their own people.

At Sikombela we were much freer. The young people would go into the local village to drink and find girls, and the villagers would come into our camp, and we would politicise them. We had a Department of Education headed by Robert Mugabe, and we organised a school for the children in the surrounding area. Christian Care sent us books. We also had a clinic established by a well-trained former nursing orderly called Samson Gwitira.

We now numbered around 400, and the need to maintain discipline became evident. We decided to set up our own police force, which we called the ‘Zimbabwe Republic Police (ZRP), for we were going to create a Republic. The presiding officer was Leopold Takawira. One of the police officers was a man called Spokes, who had been a boxer. Spokes believed that a police officer should always speak in English, of which he had little command.

We even held a party for the villagers from the surrounding area. Local women came ton the camp and brewed beer, and we slaughtered a cow.

All the top leadership was in detention together, and we remembered the Command Resolution of our first Congress in Gwelo (Gweru), which was to found an army of the Party and go to war to fight for the liberation of Zimbabwe. How were we to proceed? It would have been undemocratic for the ZANU members in exile to create a new structure without the Central Committee. Eventually, we solved this problem by issuing the Sikombela Declaration of 1965. This instrument authorised those in exile to set up the Revolutionary Council whose mandate was to prosecute the war of liberation. This Council was to consist of 17 people, five of whom represented the armed forces.

This Declaration was typed out and duly signed by Ndabaningi Sithole. Then I was given the responsibility of keeping it safe until an opportunity arose to smuggle it out. I pondered on where to hide it in the event of a raid by the Rhodesian security forces. I walked around the camp and tried to estimate what would be the outer limit of any search. At this distance from the camp, I found an ant hill, wrapped up the document and hid it there.

There was a certain Michael Mawema among us, who suddenly developed a toothache a couple of days after the signing of the declaration, and asked to be taken to Kwekwe, the town nearest the restriction camp. Nkala was later to call the incident “The tooth thing” for, after Mawema went to Kwekwe, there was indeed a raid and an extremely thorough one. An entire battalion of police came at dawn, bearing equipment for digging. They spent the whole morning searching and digging – including under the hut shared by Edson Sithole and I. But my estimate had been correct, and the document was secure in its ant hill. (Michael Mawema was later to commit suicide, but it was never conclusively proven that he did inform on us).

Soon after the raid, we had a visitor named Bango, a trade union activist who travelled frequently to Lusaka. It was decided to entrust the Declaration with this man, who duly travelled by rail to Lusaka and delivered the Declaration to Herbert Chitepo in person.

Ian Smith declared a State of Emergency on 5 November 1965. This meant that the Rhodesians could detain people under emergency regulations. My detention order was Number 1, so I was the first person to be detained under these powers. “Stated Reason for Detention: belief that … is likely to disrupt essential services and endanger public safety …”

On 8 November 1965, eight of us were rounded up and transferred to Salisbury Maximum Security Prison: Robert Mugabe, Moton Malianga, Eddison Zvobgo, George Mudukuti, Matthew Malowa, Edison Shirihuru, Fibion Shonhiwa and I. We were the people that the Security Forces considered most likely to cause trouble when UDI was declared.

Three days later, at 1.00 pm on 11 November 1965, Ian Smith proclaimed a Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI).

On 28 April 1966 the famous Battle of Sinoia (Chinhoyi) was fought, which signalled the start of the Armed Struggle. Seven men who were on a mission to perform acts of sabotage were detected by Rhodesian Forces, and were thrown into a battle situation. All were killed in that battle, but they themselves shot down an enemy aircraft and killed 25 of the enemy.

News of the battle was smuggled to us in prison, and we went wild with joy. Sithole composed a song, praising the brave men who fought at Chinhoyi.

Following UDI, Harold Wilson’s Labour Government was burdened with the Zimbabwe Crisis. Wilson adopted a maximalist position of ‘no independence before majority African role’ (NIBMAR). His insistence upon NIBMAR and his public rejection of the use of force to impose an acceptable government on Rhodesia resulted in deadlock. At the 1966 Commonwealth Conference in Lagos, Wilson was inundated with demands for action against Rhodesia. He responded that sanctions alone would resolve the matter ‘in weeks rather than in months’, a response that would haunt him and his successors. Two rounds of negotiations between Wilson and the Prime Minister of the illegal regime, Ian Smith, aboard HMS Tiger (1966) and HMS Fearless (1968), failed to end the impasse.

The years passed.

In due course, Eddison Zvobgo and Michael Mawema were released but restricted to their home area. They managed to escape to Lusaka, Zambia, where they held a press conference denouncing the armed struggle. Mawema and Zvobgo then made their way to the USA. Later, Zvobgo was to join Bishop Abel Muzorewa’s UANC.

Didymus Mutasa joined us in Salisbury Prison, and he married his wife, Gertrude, there. Later on he was released on condition that he be deported from the country, and he went to live in the UK.

In 1971, Nathan Shamuyarira, Stanley Parirewa, James Chikerema and George Nyandoro formed a new party, the Front for the Liberation of Zimbabwe (FROLIZI), in Lusaka, Zambia.

In 1974, the prison authorities moved us to the top floor of the prison, as they had discovered evidence of some digging. Our smuggling of communications now had to involve the prisoners on the lower floors as well as the wardens. Parcels were thrown from floor to floor until they reached us.

In Salisbury remand prison we began to study seriously. I tried various courses and eventually settled on a degree in Commercial Law. We were assisted in this by Christian Care, and all of us enrolled in different courses. Robert Mugabe and Leopold Takawira were among our teachers. I worked closely with Mugabe and we had a good working relationship. I emphasise this, because of what happened later, in the years after independence.

While we were in detention, his son, Nhamodzenyika, died in Ghana. As the person in charge of welfare, I wrote to Lardner Burke, the Minister of Justice, Law and Order, to have Mugabe released in order for him to go to Ghana to bury his son, but the request was denied.

There were other problems to deal with regarding the welfare of my fellow detainees. Ndabaningi Sithole began to have epileptic fits. Edson Sithole developed blisters all over his body, an allergic reaction to some medicine he was being given. George Mudukuti also developed epileptic fits, and I applied for him to be released which he eventually was.

Leopold Takawira was a wonderful man, older than the rest of us, and full of good humour, and so his death in detention was very painful to me. He had attended a seminary and was nearly ordained into priesthood, when he decided that he had to join the struggle for his country’s freedom. But he always maintained the kindness and courtesy, as well as the honesty of a man of the church. We did not pray, but I knew that he said “Grace” quietly to himself before every meal, and I am sure that he said his prayers every night. He had a calming effect on the hot-headed of us, for he was surrounded by an aura of stillness. If you sat by him at mealtimes, you always spoke more quietly.

He had developed diabetes, but this went undetected, until he fell really ill. When he complained of feeling unwell, he was placed in solitary confinement. I tried my best to get him help, but it was to no avail. We would climb up the wall of the open recreation area to look down into his cell and see how he was doing. The next morning, a sympathetic warden came to open up our cells, and informed me that Leopold Takawira had died in the night. This was on the morning of 16 June 1970.

We determined that Takawira would not be buried by the state, but at his home, and decided to raise funds towards this. We wanted him to have a decent coffin and a proper funeral ceremony. Unfortunately, we had placed James Bassoppo Moyo in charge, and he did not do as we instructed. The people attending the funeral were given no food, and Takawira was put in a prison coffin, while Moyo squandered the rest of the money.

A Lifetime of Struggle by Edgar Tekere is published by Sapes Books in Harare. The book was edited by Ibbo Mandaza. Also in the series is The Story of My Life by Joshua Nkomo, also published by Sapes.

To order any of the books, E-mail: ibbo@sapes.org.zw or Call +263-4-252961/5 OR +263-4-704921, Fax: +263-4-252964

"Cde Edgar Tekere has opened a can of worms and we need to study those worms!" For the other blogs by Rev M S Hove, please kindly click on "View my complete profile" below!

Custom Search

"MDCs PLEASE JOIN MAKONI" PLEADS TEKERE!!!

Edgar Tekere, a Zanu-PF founding member and the organisation’s secretary general until his expulsion in 1989, yesterday appealed to the Movement for Democratic Change parties to set their differences aside and rally behind Dr Simba Makoni’s bid to unseat President Robert Mugabe.

Makoni, a Zanu-PF politburo member until his dismissal from the party yesterday, announced this week that he will challenge Mugabe in next month's presidential election.

FOR MORE PLEASE CLICK HERE!!!

Makoni, a Zanu-PF politburo member until his dismissal from the party yesterday, announced this week that he will challenge Mugabe in next month's presidential election.

FOR MORE PLEASE CLICK HERE!!!

What exactly is the way forward in Zimbabwe?? Please Zimbos lets discuss! hosted by zimfinalpush.

Chat about what's on your mind. More about public chats.

|

Powered byIP2Location.com

MP3 music download website, eMusic

| Click here to unsubscribe | Privacy Policy | Terms of Use |

© 2006 eMusic.com, Inc. All rights reserved. iPod® is a registered trademark of Apple Computer, Inc. Apple is not a partner or sponsor of eMusic.com, Inc. |

|

NB: THIS IS NOT THE HOME PAGE!

Serious Mugabe......very, very serious!

"In fact....the bottom line is to die in power for fear of the people's anger!"

gostats

Technorati

Credit goes to Newzimbabwe.com (and other websites!)

These postings are mainly from newzimbabwe.com and any other sites which will be acknowledged! Just feast as you go along!

About Me

- The Radical Mindset!

- I look for "The truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth" at all times.

Wednesday, 28 February 2007

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment