Last updated: 01/20/2007 05:33:29

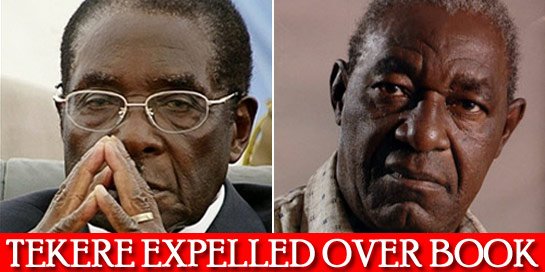

IF there’s anyone who still needed evidence that the world of power is finally collapsing around President Robert Mugabe whose tenure expires in the next 14 months that promise to be very short, nasty and brutish for him and his hangers on, it is the paranoid reaction of his propagandists to Edgar Tekere’s autobiography, A Lifetime of Struggle, published by Sapes Books in Harare last week.

Although it fails to provide new insights into vexing issues such as the deaths of Herbert Chitepo and Josiah Tongogara, the creation of the Fifth Brigade and its Gukurahundi carnage and the Unity Accord negotiations, and while the book does not flow well and fails to fully develop a number of its riveting anecdotes about happenings in the corridors of power during and after the liberation struggle, Tekere’s autobiography makes three history-marking disclosures about how Mugabe rose into and remained in power to the point of becoming a terrible liability to Zimbabwe today.

Using — many would say abusing — the public media, Mugabe’s propagandists have turned the typically dull month of January into one filled with astonishing political drama through their frenzied media defence of their embattled boss.

Yet one does not need to hold a brief for Tekere to appreciate first that he is without doubt one of Zimbabwe’s leading freedom fighters to whom we owe our national Independence, and second that he has written an informative and useful personal account of his life which was all in the struggle as captured by the title of his autobiography.

Equally important to appreciate is that Tekere is entitled to narrate the story of his lifetime of struggle in his own words through his own memory, not least because we know from the public record that his involvement in the liberation struggle was not ordinary but pivotal for better or worse.

Those who have read the autobiography are aware that it is not about Mugabe who is but one out of many individuals, some famous others not, whose lives crossed paths with Tekere during Zimbabwe’s defining moments in history. But the hysterical media reaction of Mugabe’s propagandists to Tekere’s autobiography would have those who have not read the book think that it is all about Mugabe.

Apparently Mugabe’s propagandists are furious on behalf of their thin-skinned boss that Tekere’s autobiography makes three telling disclosures that they see as fatal to whatever is left of Mugabe’s reputation and legacy. As a result, Mugabe’s propagandists have decided to raise foolish dust everywhere oblivious of the fact that raising dust in the rainy season does not work especially when the rain is on you and is pouring heavily.

The first disclosure that has annoyed Mugabe’s cronies is that Tekere says he played a leading role in paving the way for Mugabe’s rise to the leadership of Zanu PF.

Imagining itself to be correcting this disclosure, the Sunday Mail (January 14) wrote that: "Mr Tekere is … reported to have claimed that he was instrumental in catapulting President Mugabe to the helm of Zanu PF, yet the party’s wartime supreme council, the Dare reChimurenga, popularly endorsed his ascension to the party’s top post." To buttress its inane claim that goes against the grain of truth, the Sunday Mail sought the laughable rant of a hopeless polygamist clad in shabby youth service camouflage called George Rutanhire, who was exhumed from his political grave in rural Mashonaland Central and suddenly and very conveniently remembered as a veteran nationalist, former government minister and war veteran who was one of the authors of the famed Mgagao Declaration.

Betraying the ignorance of Mugabe’s propagandists who deep-throat it with defamatory nonsense, the Sunday Mail confidently but falsely reported that: "According to the war veteran (George Rutanhire), President Mugabe’s road to power began following the Mgagao Declaration which Zimbabwe’s freedom fighters wrote, denouncing the leadership of the then Zanu president the late Reverend Ndabaningi Sithole."

In the ensuing childish excitement over the political resurrection of Rutanhire, the Sunday Mail went overboard and allowed their newly found Mgagao hero to gratuitously insult and defame Tekere by alleging that he "went mad and formed his own party (Zum) in the past". How Tekere’s exercise of his protected constitutional right to form or join a political party of his choice could be said to be evidence of mental disability was of course not explained because it cannot be.

Given that the Mgagao Declaration was made in October 1975, anyone who believes that Mugabe’s road to power started then, or who believes that Sithole was deposed from the leadership of Zanu as a result of the Mgagao Declaration, is a dangerous ignoramus.

Tekere recalls in his autobiography that Mugabe’s road to power started after his return to Zimbabwe from Ghana, when he was approached and incorporated into the nationalist leadership under the NDP. To attract his incorporation, Mugabe had not demonstrated any notable leadership qualities besides his impressive proficiency in pronouncing English words with an acquired if not exaggerated accent that leaves the uncanny impression that he is a highly learned person when he is not.

As to how and when Mugabe came to head Zanu, Tekere’s autobiography recalls a fact, which has been corroborated by various independent sources, that he was elevated after the Kwekwe prison sacking of Sithole by his fellow leaders in mid-1974 in a vote spiritedly moved by Tekere and supported by Enos Nkala and Maurice Nyagumbo but opposed by Sithole himself with a cowardly abstention from Mugabe while Moton Malianga did not vote as he chaired the meeting to sack Sithole from the leadership of Zanu.

About this Tekere recalls that "the votes were cast with three in favour of the sacking, one against (Sithole), and one abstention — Mugabe. Once more Mugabe did not want to "break" with his leader. His abstention was total. He sat silently in the meeting and did not raise a finger. This is when he was appointed to head the party. For the structure was clear on this. Since the Vice-President, Leopard Takawira, had died, Mugabe, as secretary-general of the party, was the next in line."

Sithole’s dismissal from the presidency of Zanu by his colleagues in prison was communicated to all party structures, especially guerilla fighters, within and outside the country. Therefore subsequent seemingly landmark events, including the December 1974 "Nhari Rebellion", Chitepo’s assassination in March 1975, the crossing into Mozambique by Tekere and Mugabe in April 1975, the October 1975 Mgagao Declaration and the letter of January 24, 1976 from the Dare reChimurenga signed by Josiah Tongogara, Kumbirai Kangai and Rugare Gumbo, were footnotes to the sacking of Sithole and his replacement by Mugabe through an indubitably courageous motion that was moved by Tekere in the presence of both Sithole and Mugabe.

As such, only those who have been blinded by the whims and caprices of Mugabe’s personality cult and who because of that have become either malicious or sycophantic can deny that Tekere "was instrumental in catapulting Mugabe to the helm of Zanu-PF". The supporting evidence is unimpeachable.

In any event, it is clear from the public record that the October 1975 Mgagao Declaration sought to make Mugabe, who had already crossed into Mozambique with Tekere, only a spokesman and caretaker leader pending the release from prison in Zambia of Dare reChimurenga members who had been accused of murdering Chitepo and who were seen by the comrades in Mgagao as the real true leaders of the armed struggle who had inspired their declaration. That is why the Mgagao Declaration referred to Mugabe as the "…only person who can act as a middleman". The difference between a middleman and a leader is like that of night and day.

The second disclosure of Tekere’s autobiography that has sent Mugabe’s propagandists running in all directions while making fools out of themselves is that, because Mugabe is basically an insecure heartless person given to brutal vengeance, he has over the years used the political power he got with a whole lot of help from his senior nationalist colleagues to marginalise and ostracise those very same colleagues who helped him rise to the helm of Zanu PF in the first place. This is what accounts for the political misfortunes of the likes of Zanu stalwarts such as Nkala, Nyagumbo, Eddison Zvobgo and Tekere himself not to mention similar misfortunes of many others in Zapu including the late Vice-President Joshua Nkomo who was humiliated by Mugabe into submitting to a treacherous unity accord.

In the circumstances, Mugabe has come to be surrounded by dodgy political characters along with other bureaucratic and media sycophants who are known for their malice and incompetence.

The third disclosure from Tekere’s autobiography that has particularly rocked Mugabe and his propagandists beyond belief is the book’s conclusion that the blame for 90% of Zimbabwe’s ills should go to Mugabe, not the much touted economic sanctions, and that there is now a critical and urgent need for bold leadership within Zanu PF with courage to tell Mugabe that he is now a liability to Zimbabwe and that he should retire and pass the baton to a younger and more imaginative leader.

Professor Moyo MP is an Independent MP for Tsholotsho. This article was first published in the Zimbabwe Independent. He can be contacted on moyoz@mweb.co.zw

"Cde Edgar Tekere has opened a can of worms and we need to study those worms!" For the other blogs by Rev M S Hove, please kindly click on "View my complete profile" below!

Custom Search

"MDCs PLEASE JOIN MAKONI" PLEADS TEKERE!!!

Edgar Tekere, a Zanu-PF founding member and the organisation’s secretary general until his expulsion in 1989, yesterday appealed to the Movement for Democratic Change parties to set their differences aside and rally behind Dr Simba Makoni’s bid to unseat President Robert Mugabe.

Makoni, a Zanu-PF politburo member until his dismissal from the party yesterday, announced this week that he will challenge Mugabe in next month's presidential election.

FOR MORE PLEASE CLICK HERE!!!

Makoni, a Zanu-PF politburo member until his dismissal from the party yesterday, announced this week that he will challenge Mugabe in next month's presidential election.

FOR MORE PLEASE CLICK HERE!!!

What exactly is the way forward in Zimbabwe?? Please Zimbos lets discuss! hosted by zimfinalpush.

Chat about what's on your mind. More about public chats.

|

Powered byIP2Location.com

MP3 music download website, eMusic

| Click here to unsubscribe | Privacy Policy | Terms of Use |

© 2006 eMusic.com, Inc. All rights reserved. iPod® is a registered trademark of Apple Computer, Inc. Apple is not a partner or sponsor of eMusic.com, Inc. |

|

NB: THIS IS NOT THE HOME PAGE!

Serious Mugabe......very, very serious!

"In fact....the bottom line is to die in power for fear of the people's anger!"

gostats

Technorati

Credit goes to Newzimbabwe.com (and other websites!)

These postings are mainly from newzimbabwe.com and any other sites which will be acknowledged! Just feast as you go along!

About Me

- The Radical Mindset!

- I look for "The truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth" at all times.

Wednesday, 28 February 2007

Masawi threatened with action over Tekere book!

Masawi threatened with action over Tekere book

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

• Tekere unfazed by Zanu PF expulsion threats

• Hysterical reaction to Tekere belies fear

• Book shop won't sell Tekere book

• Tekere absolves Mugabe of Tongogara's killing

• 'We produced a creature that destroyed this country' - Nkala

• Tekere says Mugabe 'insecure' in new book

By Torby Chimhashu

Last updated: 01/23/2007 06:53:23

ZIMBABWE'S veteran politician Edgar Tekere has divided the ruling Zanu PF party following the publication of his new book A Lifetime of Struggle.

The party's youth wing has called for his expulsion, just under a year after his readmission.

Sources said Tekere, who during the launch of his book said he has many friends in Zanu PF much to the dismay of President Robert Mugabe's supporters, has the support of powerful ruling party stalwarts including Zanu PF secretary for administration Didymus Mutasa who pushed for his readmission and is against his ouster.

"Many influential people in Zanu PF regard Tekere as one of their own and are against his expulsion," a Zanu PF central committee member said Monday.

"Under normal circumstances, people like Mutasa and the party's spokesperson Shamuyarira should have criticised him for the attack on Mugabe. It is not a coincidence that the job to defend Mugabe was left to MDC member Patrick Kombayi and the forgotten Gorge Rutanhire."

The divisions has seen the party's youth league calling for action against Zanu PF officials who attended Tekere's book launch who include Shamuyarira's deputy Ephraim Masawi who is also Mashonaland Central provincial governor and resident minister.

Masawi as the party's deputy spokesperson has also avoided attacking Tekere.

Journalists at the state-run Herald newspaper Monday said they had sought comment from Mutasa as the party's secretary for administration over Tekere's denunciation of Mugabe but Mutasa declined to comment.

Mutasa was not returning calls Monday.

To underline the divisions, sources said although the ruling party's Manicaland Provincial Coordinating Committee (PCC) had endorsed Tekere readmission and issued him with a card, Mugabe and his two deputies, Joice Mujuru and Joseph Msika, had opposed the move by the PCC whose members include Mutasa and Zanu PF's women's boss Oppah Muchinguri, calling it "irregular".

The PCC was dealt a blow when Zanu PF said Tekere was barred from holding any position for the next five years.

The party's central committee report presented at the party's annual conference last December confirms the presidium's differed with the Manicaland PCC on Tekere.

The report said in part: "The presidency observed that Cde Tekere was already a member of the party, which was an irregularity and therefore, the national disciplinary committee was assigned to deal with the conditions Cde Tekere should meet before he enjoys the membership rights to be elected to any office in the party as provided for in the party constitution under Article 3, Section

17 (2)."

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

• Tekere unfazed by Zanu PF expulsion threats

• Hysterical reaction to Tekere belies fear

• Book shop won't sell Tekere book

• Tekere absolves Mugabe of Tongogara's killing

• 'We produced a creature that destroyed this country' - Nkala

• Tekere says Mugabe 'insecure' in new book

By Torby Chimhashu

Last updated: 01/23/2007 06:53:23

ZIMBABWE'S veteran politician Edgar Tekere has divided the ruling Zanu PF party following the publication of his new book A Lifetime of Struggle.

The party's youth wing has called for his expulsion, just under a year after his readmission.

Sources said Tekere, who during the launch of his book said he has many friends in Zanu PF much to the dismay of President Robert Mugabe's supporters, has the support of powerful ruling party stalwarts including Zanu PF secretary for administration Didymus Mutasa who pushed for his readmission and is against his ouster.

"Many influential people in Zanu PF regard Tekere as one of their own and are against his expulsion," a Zanu PF central committee member said Monday.

"Under normal circumstances, people like Mutasa and the party's spokesperson Shamuyarira should have criticised him for the attack on Mugabe. It is not a coincidence that the job to defend Mugabe was left to MDC member Patrick Kombayi and the forgotten Gorge Rutanhire."

The divisions has seen the party's youth league calling for action against Zanu PF officials who attended Tekere's book launch who include Shamuyarira's deputy Ephraim Masawi who is also Mashonaland Central provincial governor and resident minister.

Masawi as the party's deputy spokesperson has also avoided attacking Tekere.

Journalists at the state-run Herald newspaper Monday said they had sought comment from Mutasa as the party's secretary for administration over Tekere's denunciation of Mugabe but Mutasa declined to comment.

Mutasa was not returning calls Monday.

To underline the divisions, sources said although the ruling party's Manicaland Provincial Coordinating Committee (PCC) had endorsed Tekere readmission and issued him with a card, Mugabe and his two deputies, Joice Mujuru and Joseph Msika, had opposed the move by the PCC whose members include Mutasa and Zanu PF's women's boss Oppah Muchinguri, calling it "irregular".

The PCC was dealt a blow when Zanu PF said Tekere was barred from holding any position for the next five years.

The party's central committee report presented at the party's annual conference last December confirms the presidium's differed with the Manicaland PCC on Tekere.

The report said in part: "The presidency observed that Cde Tekere was already a member of the party, which was an irregularity and therefore, the national disciplinary committee was assigned to deal with the conditions Cde Tekere should meet before he enjoys the membership rights to be elected to any office in the party as provided for in the party constitution under Article 3, Section

17 (2)."

Tekere says Mugabe insecure!

Tekere says Mugabe 'insecure' in new book

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

• Mandoza is back with new album

• Knives out for Gramma boss, Metcalfe

• Tanyaradzwa premieres in London

• Calvin Gudu: The Album

• Mashakada's leg amputated

By Staff Reporter

Last updated: 01/05/2007 15:13:13

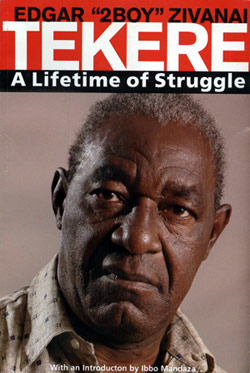

A LIFETIME of Struggle, a new book by veteran Zimbabwean politician Edgar Tekere is published next week.

Tekere, 70, served briefly in government before his popularity as a potential rival to Robert Mugabe caused their estrangement.

He founded the Zimbabwe Unity Movement (Zum) and stood against Mugabe in the 1990 election and was heavily defeated, but remained involved in politics and has recently rejoined Zanu PF.

Ibbo Mandaza, a veteran journalist and academic who wrote Tekere's biography said Tekere shows Mugabe as a "weak character" in the 200-page book, the second by a leading figure in Zimbabwe's war of independence after Joshua Nkomo's The Story of My Life.

"Tekere focuses on the liberation struggle itself, the military aspect of it," Mandaza told New Zimbabwe.com Thursday. "It reveals how that militarism of the liberation war has overflown into the current situation where we have violence of the state."

Mandaza said Tekere also shows in great detail how the late Josiah Tongogara was "completely in charge" on the liberation war effort while Mugabe's role was "very marginal".

While acknowledging that the book reveals a lot of "bitterness" by Tekere at his treatment by Mugabe, Mandaza insists that the book provides an authoritative history of the liberation war and the character of Robert Mugabe.

He said: "Tekere shows Mugabe as a weak character. He also comes across as an unreliable and calculating individual keen on long term strategies where people are used variously like Enos Nkala, Maurice Nyagumbo and Tekere himself to achieve set ends.

"Tekere also portrays Mugabe as manipulative and therefore, insecure which explains his desire to stay in power. Tekere also says Mugabe has an inability to see beyond himself.

"This book is an eye-opener and in a way, it explains the nature of the state today."

When Zanu won the 1980 elections, Tekere was appointed Manpower Planning Minister in Mugabe's Cabinet. He followed his appointment by making a series of outspoken speeches which went far beyond government policy.

Tekere's consistent criticism of corruption resulted in his expulsion from Zanu PF in 1988. When Mugabe voiced his belief that Zimbabwe would be better governed as a one party state, Tekere strongly disagreed, saying "a one-party state was never one of the founding principles of Zanu PF and experience in Africa has shown that it brought the evils of nepotism, corruption and inefficiency".

He ran against Robert Mugabe in the 1990 Presidential race as the candidate of the Zimbabwe Unity Movement, offering a broadly free market platform against Mugabe's communist-style economic planning.

won the election on April 1, 1990 receiving 2,026,976 votes while Tekere only got 413,840 (16% of the vote). At the simultaneous Parliamentary elections the ZUM won 20% of the vote but only two seats in the House of Assembly.

He recently rejoined Zanu PF but is barred from holding a position.

Meanwhile, Mandaza also revealed Sapes Books are reprinting the biography of Joshua Nkomo, The Story of My Life.

A Lifetime of Struggle is published by Sapes Books. You can e-mail info@sapes.org.zw for a copy. The book will be distributed by African Book Collectors in London (click here)

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

• Mandoza is back with new album

• Knives out for Gramma boss, Metcalfe

• Tanyaradzwa premieres in London

• Calvin Gudu: The Album

• Mashakada's leg amputated

By Staff Reporter

Last updated: 01/05/2007 15:13:13

A LIFETIME of Struggle, a new book by veteran Zimbabwean politician Edgar Tekere is published next week.

Tekere, 70, served briefly in government before his popularity as a potential rival to Robert Mugabe caused their estrangement.

He founded the Zimbabwe Unity Movement (Zum) and stood against Mugabe in the 1990 election and was heavily defeated, but remained involved in politics and has recently rejoined Zanu PF.

Ibbo Mandaza, a veteran journalist and academic who wrote Tekere's biography said Tekere shows Mugabe as a "weak character" in the 200-page book, the second by a leading figure in Zimbabwe's war of independence after Joshua Nkomo's The Story of My Life.

"Tekere focuses on the liberation struggle itself, the military aspect of it," Mandaza told New Zimbabwe.com Thursday. "It reveals how that militarism of the liberation war has overflown into the current situation where we have violence of the state."

Mandaza said Tekere also shows in great detail how the late Josiah Tongogara was "completely in charge" on the liberation war effort while Mugabe's role was "very marginal".

While acknowledging that the book reveals a lot of "bitterness" by Tekere at his treatment by Mugabe, Mandaza insists that the book provides an authoritative history of the liberation war and the character of Robert Mugabe.

He said: "Tekere shows Mugabe as a weak character. He also comes across as an unreliable and calculating individual keen on long term strategies where people are used variously like Enos Nkala, Maurice Nyagumbo and Tekere himself to achieve set ends.

"Tekere also portrays Mugabe as manipulative and therefore, insecure which explains his desire to stay in power. Tekere also says Mugabe has an inability to see beyond himself.

"This book is an eye-opener and in a way, it explains the nature of the state today."

When Zanu won the 1980 elections, Tekere was appointed Manpower Planning Minister in Mugabe's Cabinet. He followed his appointment by making a series of outspoken speeches which went far beyond government policy.

Tekere's consistent criticism of corruption resulted in his expulsion from Zanu PF in 1988. When Mugabe voiced his belief that Zimbabwe would be better governed as a one party state, Tekere strongly disagreed, saying "a one-party state was never one of the founding principles of Zanu PF and experience in Africa has shown that it brought the evils of nepotism, corruption and inefficiency".

He ran against Robert Mugabe in the 1990 Presidential race as the candidate of the Zimbabwe Unity Movement, offering a broadly free market platform against Mugabe's communist-style economic planning.

won the election on April 1, 1990 receiving 2,026,976 votes while Tekere only got 413,840 (16% of the vote). At the simultaneous Parliamentary elections the ZUM won 20% of the vote but only two seats in the House of Assembly.

He recently rejoined Zanu PF but is barred from holding a position.

Meanwhile, Mandaza also revealed Sapes Books are reprinting the biography of Joshua Nkomo, The Story of My Life.

A Lifetime of Struggle is published by Sapes Books. You can e-mail info@sapes.org.zw for a copy. The book will be distributed by African Book Collectors in London (click here)

And so the armed struggle began...

And so the armed struggle began...

In his new book, A Lifetime of Struggle, Edgar Tekere delves into his controversial Life starting with his humble upbringing as the son of a Makoni Princess, his odssey into Mozambique at the side of Robert Mugabe, and his rise to prominence within the liberation movement of Zimbabwe.

New Zimbabwe.com continues with its exclusive extracts from the book which captures some of the most extra-ordinary events during the bush war that led to the country’s independence:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Last updated: 02/28/2007 04:03:59

ZANU was banned in August 1964, soon after the Congress of May of that year, in which the Armed Struggle was launched, but this time operations were already underway, led by William Ndangana. Operations began in the towns of Melsetter, Nyanyadzi and Mvuma in central and eastern Zimbabwe.

On 4 July 1964 Ndangana set up a roadblock and, with Victor Mlambo, James Dhlamini and Master Tresha, killed a white man of Afrikaans descent called Petros Oberholtzer in the Chimanimani farming area of eastern Zimbabwe. Ndananga and his men came to be known as the ‘Crocodile Gang’.

After this act, Mlambo and Dhlamini crossed the border into Mozambique, but the police there captured them and brought them back to Southern Rhodesia, where they were tried and hanged at Salisbury Central Prison. Ndananga himself was smuggled into Malawi. Master Tresha was also captured, but sentenced to life imprisonment as he was too young to suffer the death penalty.

After the killing of Petros Oberholtzer I had a brief brush with the police. Although I was not then operational, I held the post of Deputy Secretary for Youth -- and youth are considered the lifeblood of any war effort. I happened to be in the Chipinge area (I had been fired from my Gweru job because of my political activism), when I was arrested and locked up at Nyanyadzi Police Camp. The police suspected that I was part of the ‘Crocodile Gang’. From Nyanyadzi I was transferred to Harare Central Police Station, where I was interrogated by the Special Branch. They were tryhing to convict me of the murder of Petros Oberholtzer.

Eventually, as they were unable to build a case against me, I was released.

After the banning of ZANU in 1964, the Rhodesian security forces began rounding up all Party members. For a while I remained free, in hiding in a run-down neighbourhood of Salisbury known as Kopje. In September, the trial of Ndabaningi Sithole took place, and I was assigned to look after Herbert Chitepo, who had flown in from Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, to defend Sithole. Chitepo was booked into the Jameson Hotel, but I, who drove a small Morris Minor 1000 at that time, would pick him up and take him elsewhere in case he was kidnapped by the Rhodesians. As soon as the trial was over, I rushed him to the airport and he was immediately on his way.

I was caught again by the police in central Salisbury, along what is now Julius Nyerere Way. Since I was not handcuffed I managed to sprint through the busy traffic and disappear for a few more days, but the next was closing in.

A few days after this incident, I was run to ground at my parents’ home at St Mary’s, near Salisbury, on 16 October of that year. I was taken to Salisbury Central Police Station. There, I met Abisha Mudzingwa, another young ZANU man.

We were then transported by road to Gwelo (Gweru) Prison, where we joined Joshua Nkomo, Josiah Chinamano, Daniel Madzimbamuto and others from the ZAPU group. Daniel Madzimbamuto wanted to kill us, accusing us of the murder of his brother, who had been killed during the in-fighting between ZANU and ZAPU. When he was killed, I and my group had been descending on other towns from Gweru to fight with ZAPU members. Nkomo took us into his cell for our protection.

During the course of that year, 1964, Nkomo challenged the detention order and won the case. But instead of releasing us, we were issued with Restriction Orders.

The two groups, ZANU and ZAPU, were divided between two different holding centres, Gonakudzingwa for ZAPU members and Wha Wha for ZANU. So, Mudzingwa and I were transported to Wha Wha.

At Wha Wha were Basoppo-Moyo, Simon Muzenda, Crispen Mandizvidza, Morton Malianga, Edson Sithole, and Amos Kombo, among others.

The camps were unlike conventional prisons: they had no walls, no bars, but were located right in the bush. We knew that anyone who tried to walk away would not survive the journey. We named the place ‘Snake Park’ (after a tourist attraction in Salisbury) because of the number of snakes infesting the camp.

Barracks were provided for the restrictees to sleep in, but those who required more privacy were allowed to build their own thatch-roofed huts. Edson Sithole and I built one for ourselves. We formed a committee to manage our affairs, and called it the ‘Village Committee’. Our spokesperson was Crispen Mandizvidza. The police reservists would come once a week to make sure all was in order, and to bring our rations.

Not long after we arrived, Robert Mugabe, Leopold Takawira and Eddison Zvobgo joined us from Salisbury Prison, making up the entire complement of the ZANU leadership.

Christian Care sent us books and arranged for us to study. Edson Sithole was studying Law.

Meanwhile, in 1964, Ian Smith of the Rhodesian Front had been elected as Prime Minister of Rhodesia. Smith was famous for pronouncing that blacks would not achieve equality, “not in a thousand years.” The British, who were committed to a gradual process of slowly preparing blacks for independence – too slowly for us – were worried by this development, and on 1 March 1965, I, Leopold Takawira and others were taken to New Sarum air base near Salisbury for discussions with Arthur Bottomley, British Foreign and Commonwealth Secretary, and Lord Gardner. These were not helpful, and we did not even listen to their proposals.

On 15 June 1965 we were served with new orders and were transferred to Sikombela Restriction Area in the district of Gokwe, in Midlands Province.

Harold Wilson came to Salisbury, and I was part of the delegation sent to discuss a looming Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) by Smith. Wilson told us that if Smith did declare a UDI, we should not expect the British to intervene against their own people.

At Sikombela we were much freer. The young people would go into the local village to drink and find girls, and the villagers would come into our camp, and we would politicise them. We had a Department of Education headed by Robert Mugabe, and we organised a school for the children in the surrounding area. Christian Care sent us books. We also had a clinic established by a well-trained former nursing orderly called Samson Gwitira.

We now numbered around 400, and the need to maintain discipline became evident. We decided to set up our own police force, which we called the ‘Zimbabwe Republic Police (ZRP), for we were going to create a Republic. The presiding officer was Leopold Takawira. One of the police officers was a man called Spokes, who had been a boxer. Spokes believed that a police officer should always speak in English, of which he had little command.

We even held a party for the villagers from the surrounding area. Local women came ton the camp and brewed beer, and we slaughtered a cow.

All the top leadership was in detention together, and we remembered the Command Resolution of our first Congress in Gwelo (Gweru), which was to found an army of the Party and go to war to fight for the liberation of Zimbabwe. How were we to proceed? It would have been undemocratic for the ZANU members in exile to create a new structure without the Central Committee. Eventually, we solved this problem by issuing the Sikombela Declaration of 1965. This instrument authorised those in exile to set up the Revolutionary Council whose mandate was to prosecute the war of liberation. This Council was to consist of 17 people, five of whom represented the armed forces.

This Declaration was typed out and duly signed by Ndabaningi Sithole. Then I was given the responsibility of keeping it safe until an opportunity arose to smuggle it out. I pondered on where to hide it in the event of a raid by the Rhodesian security forces. I walked around the camp and tried to estimate what would be the outer limit of any search. At this distance from the camp, I found an ant hill, wrapped up the document and hid it there.

There was a certain Michael Mawema among us, who suddenly developed a toothache a couple of days after the signing of the declaration, and asked to be taken to Kwekwe, the town nearest the restriction camp. Nkala was later to call the incident “The tooth thing” for, after Mawema went to Kwekwe, there was indeed a raid and an extremely thorough one. An entire battalion of police came at dawn, bearing equipment for digging. They spent the whole morning searching and digging – including under the hut shared by Edson Sithole and I. But my estimate had been correct, and the document was secure in its ant hill. (Michael Mawema was later to commit suicide, but it was never conclusively proven that he did inform on us).

Soon after the raid, we had a visitor named Bango, a trade union activist who travelled frequently to Lusaka. It was decided to entrust the Declaration with this man, who duly travelled by rail to Lusaka and delivered the Declaration to Herbert Chitepo in person.

Ian Smith declared a State of Emergency on 5 November 1965. This meant that the Rhodesians could detain people under emergency regulations. My detention order was Number 1, so I was the first person to be detained under these powers. “Stated Reason for Detention: belief that … is likely to disrupt essential services and endanger public safety …”

On 8 November 1965, eight of us were rounded up and transferred to Salisbury Maximum Security Prison: Robert Mugabe, Moton Malianga, Eddison Zvobgo, George Mudukuti, Matthew Malowa, Edison Shirihuru, Fibion Shonhiwa and I. We were the people that the Security Forces considered most likely to cause trouble when UDI was declared.

Three days later, at 1.00 pm on 11 November 1965, Ian Smith proclaimed a Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI).

On 28 April 1966 the famous Battle of Sinoia (Chinhoyi) was fought, which signalled the start of the Armed Struggle. Seven men who were on a mission to perform acts of sabotage were detected by Rhodesian Forces, and were thrown into a battle situation. All were killed in that battle, but they themselves shot down an enemy aircraft and killed 25 of the enemy.

News of the battle was smuggled to us in prison, and we went wild with joy. Sithole composed a song, praising the brave men who fought at Chinhoyi.

Following UDI, Harold Wilson’s Labour Government was burdened with the Zimbabwe Crisis. Wilson adopted a maximalist position of ‘no independence before majority African role’ (NIBMAR). His insistence upon NIBMAR and his public rejection of the use of force to impose an acceptable government on Rhodesia resulted in deadlock. At the 1966 Commonwealth Conference in Lagos, Wilson was inundated with demands for action against Rhodesia. He responded that sanctions alone would resolve the matter ‘in weeks rather than in months’, a response that would haunt him and his successors. Two rounds of negotiations between Wilson and the Prime Minister of the illegal regime, Ian Smith, aboard HMS Tiger (1966) and HMS Fearless (1968), failed to end the impasse.

The years passed.

In due course, Eddison Zvobgo and Michael Mawema were released but restricted to their home area. They managed to escape to Lusaka, Zambia, where they held a press conference denouncing the armed struggle. Mawema and Zvobgo then made their way to the USA. Later, Zvobgo was to join Bishop Abel Muzorewa’s UANC.

Didymus Mutasa joined us in Salisbury Prison, and he married his wife, Gertrude, there. Later on he was released on condition that he be deported from the country, and he went to live in the UK.

In 1971, Nathan Shamuyarira, Stanley Parirewa, James Chikerema and George Nyandoro formed a new party, the Front for the Liberation of Zimbabwe (FROLIZI), in Lusaka, Zambia.

In 1974, the prison authorities moved us to the top floor of the prison, as they had discovered evidence of some digging. Our smuggling of communications now had to involve the prisoners on the lower floors as well as the wardens. Parcels were thrown from floor to floor until they reached us.

In Salisbury remand prison we began to study seriously. I tried various courses and eventually settled on a degree in Commercial Law. We were assisted in this by Christian Care, and all of us enrolled in different courses. Robert Mugabe and Leopold Takawira were among our teachers. I worked closely with Mugabe and we had a good working relationship. I emphasise this, because of what happened later, in the years after independence.

While we were in detention, his son, Nhamodzenyika, died in Ghana. As the person in charge of welfare, I wrote to Lardner Burke, the Minister of Justice, Law and Order, to have Mugabe released in order for him to go to Ghana to bury his son, but the request was denied.

There were other problems to deal with regarding the welfare of my fellow detainees. Ndabaningi Sithole began to have epileptic fits. Edson Sithole developed blisters all over his body, an allergic reaction to some medicine he was being given. George Mudukuti also developed epileptic fits, and I applied for him to be released which he eventually was.

Leopold Takawira was a wonderful man, older than the rest of us, and full of good humour, and so his death in detention was very painful to me. He had attended a seminary and was nearly ordained into priesthood, when he decided that he had to join the struggle for his country’s freedom. But he always maintained the kindness and courtesy, as well as the honesty of a man of the church. We did not pray, but I knew that he said “Grace” quietly to himself before every meal, and I am sure that he said his prayers every night. He had a calming effect on the hot-headed of us, for he was surrounded by an aura of stillness. If you sat by him at mealtimes, you always spoke more quietly.

He had developed diabetes, but this went undetected, until he fell really ill. When he complained of feeling unwell, he was placed in solitary confinement. I tried my best to get him help, but it was to no avail. We would climb up the wall of the open recreation area to look down into his cell and see how he was doing. The next morning, a sympathetic warden came to open up our cells, and informed me that Leopold Takawira had died in the night. This was on the morning of 16 June 1970.

We determined that Takawira would not be buried by the state, but at his home, and decided to raise funds towards this. We wanted him to have a decent coffin and a proper funeral ceremony. Unfortunately, we had placed James Bassoppo Moyo in charge, and he did not do as we instructed. The people attending the funeral were given no food, and Takawira was put in a prison coffin, while Moyo squandered the rest of the money.

A Lifetime of Struggle by Edgar Tekere is published by Sapes Books in Harare. The book was edited by Ibbo Mandaza. Also in the series is The Story of My Life by Joshua Nkomo, also published by Sapes.

To order any of the books, E-mail: ibbo@sapes.org.zw or Call +263-4-252961/5 OR +263-4-704921, Fax: +263-4-252964

In his new book, A Lifetime of Struggle, Edgar Tekere delves into his controversial Life starting with his humble upbringing as the son of a Makoni Princess, his odssey into Mozambique at the side of Robert Mugabe, and his rise to prominence within the liberation movement of Zimbabwe.

New Zimbabwe.com continues with its exclusive extracts from the book which captures some of the most extra-ordinary events during the bush war that led to the country’s independence:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Last updated: 02/28/2007 04:03:59

ZANU was banned in August 1964, soon after the Congress of May of that year, in which the Armed Struggle was launched, but this time operations were already underway, led by William Ndangana. Operations began in the towns of Melsetter, Nyanyadzi and Mvuma in central and eastern Zimbabwe.

On 4 July 1964 Ndangana set up a roadblock and, with Victor Mlambo, James Dhlamini and Master Tresha, killed a white man of Afrikaans descent called Petros Oberholtzer in the Chimanimani farming area of eastern Zimbabwe. Ndananga and his men came to be known as the ‘Crocodile Gang’.

After this act, Mlambo and Dhlamini crossed the border into Mozambique, but the police there captured them and brought them back to Southern Rhodesia, where they were tried and hanged at Salisbury Central Prison. Ndananga himself was smuggled into Malawi. Master Tresha was also captured, but sentenced to life imprisonment as he was too young to suffer the death penalty.

After the killing of Petros Oberholtzer I had a brief brush with the police. Although I was not then operational, I held the post of Deputy Secretary for Youth -- and youth are considered the lifeblood of any war effort. I happened to be in the Chipinge area (I had been fired from my Gweru job because of my political activism), when I was arrested and locked up at Nyanyadzi Police Camp. The police suspected that I was part of the ‘Crocodile Gang’. From Nyanyadzi I was transferred to Harare Central Police Station, where I was interrogated by the Special Branch. They were tryhing to convict me of the murder of Petros Oberholtzer.

Eventually, as they were unable to build a case against me, I was released.

After the banning of ZANU in 1964, the Rhodesian security forces began rounding up all Party members. For a while I remained free, in hiding in a run-down neighbourhood of Salisbury known as Kopje. In September, the trial of Ndabaningi Sithole took place, and I was assigned to look after Herbert Chitepo, who had flown in from Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, to defend Sithole. Chitepo was booked into the Jameson Hotel, but I, who drove a small Morris Minor 1000 at that time, would pick him up and take him elsewhere in case he was kidnapped by the Rhodesians. As soon as the trial was over, I rushed him to the airport and he was immediately on his way.

I was caught again by the police in central Salisbury, along what is now Julius Nyerere Way. Since I was not handcuffed I managed to sprint through the busy traffic and disappear for a few more days, but the next was closing in.

A few days after this incident, I was run to ground at my parents’ home at St Mary’s, near Salisbury, on 16 October of that year. I was taken to Salisbury Central Police Station. There, I met Abisha Mudzingwa, another young ZANU man.

We were then transported by road to Gwelo (Gweru) Prison, where we joined Joshua Nkomo, Josiah Chinamano, Daniel Madzimbamuto and others from the ZAPU group. Daniel Madzimbamuto wanted to kill us, accusing us of the murder of his brother, who had been killed during the in-fighting between ZANU and ZAPU. When he was killed, I and my group had been descending on other towns from Gweru to fight with ZAPU members. Nkomo took us into his cell for our protection.

During the course of that year, 1964, Nkomo challenged the detention order and won the case. But instead of releasing us, we were issued with Restriction Orders.

The two groups, ZANU and ZAPU, were divided between two different holding centres, Gonakudzingwa for ZAPU members and Wha Wha for ZANU. So, Mudzingwa and I were transported to Wha Wha.

At Wha Wha were Basoppo-Moyo, Simon Muzenda, Crispen Mandizvidza, Morton Malianga, Edson Sithole, and Amos Kombo, among others.

The camps were unlike conventional prisons: they had no walls, no bars, but were located right in the bush. We knew that anyone who tried to walk away would not survive the journey. We named the place ‘Snake Park’ (after a tourist attraction in Salisbury) because of the number of snakes infesting the camp.

Barracks were provided for the restrictees to sleep in, but those who required more privacy were allowed to build their own thatch-roofed huts. Edson Sithole and I built one for ourselves. We formed a committee to manage our affairs, and called it the ‘Village Committee’. Our spokesperson was Crispen Mandizvidza. The police reservists would come once a week to make sure all was in order, and to bring our rations.

Not long after we arrived, Robert Mugabe, Leopold Takawira and Eddison Zvobgo joined us from Salisbury Prison, making up the entire complement of the ZANU leadership.

Christian Care sent us books and arranged for us to study. Edson Sithole was studying Law.

Meanwhile, in 1964, Ian Smith of the Rhodesian Front had been elected as Prime Minister of Rhodesia. Smith was famous for pronouncing that blacks would not achieve equality, “not in a thousand years.” The British, who were committed to a gradual process of slowly preparing blacks for independence – too slowly for us – were worried by this development, and on 1 March 1965, I, Leopold Takawira and others were taken to New Sarum air base near Salisbury for discussions with Arthur Bottomley, British Foreign and Commonwealth Secretary, and Lord Gardner. These were not helpful, and we did not even listen to their proposals.

On 15 June 1965 we were served with new orders and were transferred to Sikombela Restriction Area in the district of Gokwe, in Midlands Province.

Harold Wilson came to Salisbury, and I was part of the delegation sent to discuss a looming Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) by Smith. Wilson told us that if Smith did declare a UDI, we should not expect the British to intervene against their own people.

At Sikombela we were much freer. The young people would go into the local village to drink and find girls, and the villagers would come into our camp, and we would politicise them. We had a Department of Education headed by Robert Mugabe, and we organised a school for the children in the surrounding area. Christian Care sent us books. We also had a clinic established by a well-trained former nursing orderly called Samson Gwitira.

We now numbered around 400, and the need to maintain discipline became evident. We decided to set up our own police force, which we called the ‘Zimbabwe Republic Police (ZRP), for we were going to create a Republic. The presiding officer was Leopold Takawira. One of the police officers was a man called Spokes, who had been a boxer. Spokes believed that a police officer should always speak in English, of which he had little command.

We even held a party for the villagers from the surrounding area. Local women came ton the camp and brewed beer, and we slaughtered a cow.

All the top leadership was in detention together, and we remembered the Command Resolution of our first Congress in Gwelo (Gweru), which was to found an army of the Party and go to war to fight for the liberation of Zimbabwe. How were we to proceed? It would have been undemocratic for the ZANU members in exile to create a new structure without the Central Committee. Eventually, we solved this problem by issuing the Sikombela Declaration of 1965. This instrument authorised those in exile to set up the Revolutionary Council whose mandate was to prosecute the war of liberation. This Council was to consist of 17 people, five of whom represented the armed forces.

This Declaration was typed out and duly signed by Ndabaningi Sithole. Then I was given the responsibility of keeping it safe until an opportunity arose to smuggle it out. I pondered on where to hide it in the event of a raid by the Rhodesian security forces. I walked around the camp and tried to estimate what would be the outer limit of any search. At this distance from the camp, I found an ant hill, wrapped up the document and hid it there.

There was a certain Michael Mawema among us, who suddenly developed a toothache a couple of days after the signing of the declaration, and asked to be taken to Kwekwe, the town nearest the restriction camp. Nkala was later to call the incident “The tooth thing” for, after Mawema went to Kwekwe, there was indeed a raid and an extremely thorough one. An entire battalion of police came at dawn, bearing equipment for digging. They spent the whole morning searching and digging – including under the hut shared by Edson Sithole and I. But my estimate had been correct, and the document was secure in its ant hill. (Michael Mawema was later to commit suicide, but it was never conclusively proven that he did inform on us).

Soon after the raid, we had a visitor named Bango, a trade union activist who travelled frequently to Lusaka. It was decided to entrust the Declaration with this man, who duly travelled by rail to Lusaka and delivered the Declaration to Herbert Chitepo in person.

Ian Smith declared a State of Emergency on 5 November 1965. This meant that the Rhodesians could detain people under emergency regulations. My detention order was Number 1, so I was the first person to be detained under these powers. “Stated Reason for Detention: belief that … is likely to disrupt essential services and endanger public safety …”

On 8 November 1965, eight of us were rounded up and transferred to Salisbury Maximum Security Prison: Robert Mugabe, Moton Malianga, Eddison Zvobgo, George Mudukuti, Matthew Malowa, Edison Shirihuru, Fibion Shonhiwa and I. We were the people that the Security Forces considered most likely to cause trouble when UDI was declared.

Three days later, at 1.00 pm on 11 November 1965, Ian Smith proclaimed a Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI).

On 28 April 1966 the famous Battle of Sinoia (Chinhoyi) was fought, which signalled the start of the Armed Struggle. Seven men who were on a mission to perform acts of sabotage were detected by Rhodesian Forces, and were thrown into a battle situation. All were killed in that battle, but they themselves shot down an enemy aircraft and killed 25 of the enemy.

News of the battle was smuggled to us in prison, and we went wild with joy. Sithole composed a song, praising the brave men who fought at Chinhoyi.

Following UDI, Harold Wilson’s Labour Government was burdened with the Zimbabwe Crisis. Wilson adopted a maximalist position of ‘no independence before majority African role’ (NIBMAR). His insistence upon NIBMAR and his public rejection of the use of force to impose an acceptable government on Rhodesia resulted in deadlock. At the 1966 Commonwealth Conference in Lagos, Wilson was inundated with demands for action against Rhodesia. He responded that sanctions alone would resolve the matter ‘in weeks rather than in months’, a response that would haunt him and his successors. Two rounds of negotiations between Wilson and the Prime Minister of the illegal regime, Ian Smith, aboard HMS Tiger (1966) and HMS Fearless (1968), failed to end the impasse.

The years passed.

In due course, Eddison Zvobgo and Michael Mawema were released but restricted to their home area. They managed to escape to Lusaka, Zambia, where they held a press conference denouncing the armed struggle. Mawema and Zvobgo then made their way to the USA. Later, Zvobgo was to join Bishop Abel Muzorewa’s UANC.

Didymus Mutasa joined us in Salisbury Prison, and he married his wife, Gertrude, there. Later on he was released on condition that he be deported from the country, and he went to live in the UK.

In 1971, Nathan Shamuyarira, Stanley Parirewa, James Chikerema and George Nyandoro formed a new party, the Front for the Liberation of Zimbabwe (FROLIZI), in Lusaka, Zambia.

In 1974, the prison authorities moved us to the top floor of the prison, as they had discovered evidence of some digging. Our smuggling of communications now had to involve the prisoners on the lower floors as well as the wardens. Parcels were thrown from floor to floor until they reached us.

In Salisbury remand prison we began to study seriously. I tried various courses and eventually settled on a degree in Commercial Law. We were assisted in this by Christian Care, and all of us enrolled in different courses. Robert Mugabe and Leopold Takawira were among our teachers. I worked closely with Mugabe and we had a good working relationship. I emphasise this, because of what happened later, in the years after independence.

While we were in detention, his son, Nhamodzenyika, died in Ghana. As the person in charge of welfare, I wrote to Lardner Burke, the Minister of Justice, Law and Order, to have Mugabe released in order for him to go to Ghana to bury his son, but the request was denied.

There were other problems to deal with regarding the welfare of my fellow detainees. Ndabaningi Sithole began to have epileptic fits. Edson Sithole developed blisters all over his body, an allergic reaction to some medicine he was being given. George Mudukuti also developed epileptic fits, and I applied for him to be released which he eventually was.

Leopold Takawira was a wonderful man, older than the rest of us, and full of good humour, and so his death in detention was very painful to me. He had attended a seminary and was nearly ordained into priesthood, when he decided that he had to join the struggle for his country’s freedom. But he always maintained the kindness and courtesy, as well as the honesty of a man of the church. We did not pray, but I knew that he said “Grace” quietly to himself before every meal, and I am sure that he said his prayers every night. He had a calming effect on the hot-headed of us, for he was surrounded by an aura of stillness. If you sat by him at mealtimes, you always spoke more quietly.

He had developed diabetes, but this went undetected, until he fell really ill. When he complained of feeling unwell, he was placed in solitary confinement. I tried my best to get him help, but it was to no avail. We would climb up the wall of the open recreation area to look down into his cell and see how he was doing. The next morning, a sympathetic warden came to open up our cells, and informed me that Leopold Takawira had died in the night. This was on the morning of 16 June 1970.

We determined that Takawira would not be buried by the state, but at his home, and decided to raise funds towards this. We wanted him to have a decent coffin and a proper funeral ceremony. Unfortunately, we had placed James Bassoppo Moyo in charge, and he did not do as we instructed. The people attending the funeral were given no food, and Takawira was put in a prison coffin, while Moyo squandered the rest of the money.

A Lifetime of Struggle by Edgar Tekere is published by Sapes Books in Harare. The book was edited by Ibbo Mandaza. Also in the series is The Story of My Life by Joshua Nkomo, also published by Sapes.

To order any of the books, E-mail: ibbo@sapes.org.zw or Call +263-4-252961/5 OR +263-4-704921, Fax: +263-4-252964

Tuesday, 27 February 2007

More on Tekere's Book!

EDGAR TEKERE: THE BOOK THEY DON'T WANT YOU TO READ

Mugabe's women, and the ZAPU split

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

• The people who saved me from poverty

• Masawi threatened over Tekere book

• Tekere unfazed by Zanu PF expulsion threats

• Hysterical reaction to Tekere belies fear

• Book shop won't sell Tekere book

• Tekere absolves Mugabe of Tongogara's killing

• 'We produced a creature that destroyed this country' - Nkala

• Tekere says Mugabe 'insecure' in new book

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In his new book, A Lifetime of Struggle, Edgar Tekere delves into his controversial Life starting with his humble upbringing as the son of a Makoni Princess, his odssey into Mozambique at the side of Robert Mugabe, and his rise to prominence within the liberation movement of Zimbabwe.

New Zimbabwe.com continues with its exclusive extracts from the book which captures some of the most extra-ordinary events during the bush war that led to the country’s independence:

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Last updated: 02/27/2007 03:06:16

FROM 1953 to 1958, the Southern Rhodesian government of Garfield Todd attempted to introduce liberal reforms to increase educational rights for the black majority but Todd was forced from power when he attempted to expand the number of blacks eligible to vote from 2% to 16%. Taking their cue from the liberal Todd, the early national movements (including the Southern Rhodesia African National Congress led by Rev Thompson Samkange, the British African Voice Association, led by Benjamin Burombo and the Reformed Industrial and Commercial Workers’ Union, led by Charles Mzingeli), accepted the reality of settler colonial rule, but opposed racial discrimination within the system.

The governments that followed Todd’s became increasingly repressive, introducing laws such as the Law and Order (Maintenance) Act of 1960 and the Emergency Powers Act which restricted the rights of the black African majority. Increasing repression, instead of cowing the people, radicalised subsequent political formations.

In 1958, discussion in our party, the ANC, focused on the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland were opposed to the Federation, as they saw that all the resources were concentrated in Southern Rhodesia, which used the other two countries merely as sources of revenue, mainly copper and cheap labour.

In Nyasaland (as Malawi was then known), the Nyasaland African National Congress was led by Henry Chipembere, Dunduza Chisiza, Orton Chirwa and others. Hastings Banda was then in Britain, and had established contact with Dr Kwame Nkrumah. The ANC asked him to return and take over the leadership. On his way back to Nyasaland, Banda travelled via Salisbury, where he was hosted by George Nyandoro in his home in Highfield Township. He spoke at Cyril Jennings Hall in the same Township, and my car was used to drive Dr Banda.

By the time Banda arrived home, Nyasaland was aflame. The ANC presented him with a broom upon his welcome at Chileka Airport “with which to sweep away the stupid Federation.” The fervour in Nyasaland also swept us up, and we joined the fight against Federation.

In Northern Rhodesia (Zambia), the ANC leader of the time, Harry Kumbula, was not as strong a personality as Banda, and thus Kenneth Kaunda and others broke away from the ANC to form the United National Independence Party (UNIP).

In 1960, the National Democratic Party was formed, since the ANC was banned in February 1959. Its constitution was written from prison by Edson Sithole. Michael Mawema was elected leader. Other leaders included Leopold Takawira, Enos Nkala, Moton Malianga and Jason Z Moyo. That was when I first met Sabina Mugabe. Robert Mugabe had not yet returned from Ghana where he was a teacher.

There were many colourful characters in the Party: Paul Mushonga was a businessman who gave most of his income to the party. James Chiweshe was another businessman, proud and jocular. Peter Mutandwa was the organising secretary of the Party, and a very religious man. Mutandwa was a diabetic, and thus whenever he was arrested he had to be accommodated in Class 2 cells, meant for persons of mixed race, and was the first African to qualify for membership of the Institute of Chartered Secretaries.

The National Democratic Party (NDP) demanded majority rule, universal adult suffrage, and impendence from Britain. For the first time, we had a clear programme, but we relied on Constitutional conferences with Britain as the principal means for attaining independence.

At first the NDP drew its support from the urban population, and was slower to gain support in the rural areas. Rural people thought our demands were too radical and did not see how we could achieve them. The ANC had been more of a pressure group than a political party, concentrating mainly on land issues.

My own position was that of secretary of the Salisbury District Council. The chair was Stanley Parirewa, and the publicity secretary was Noel Mukono, a highly qualified journalist who worked for Drum Magazine and who subsequently joined forces with Ndabaningi Sithole, went into exile through Malawi, and became part of the Dare in Lusaka in the 1960s.

In February 1961, a conference to review Southern Rhodesia’s Constitution opened in Salisbury with British Commonwealth Secretary, Mr Duncan Sandys, as chair. The conference agreed on the removal of reservations in return for a Declaration of Rights and appointment of a Constitutional Council. Parliament was to be enlarged from 30 to 45 members, and Africans were to be given representation through a ‘B’ Roll. Joshua Nkomo, with Herbert Chitepo as legal adviser, attended the conference, and accepted the proposed revisions. In those early days, Chitepo was still something of a “liberal,” and only later was to see the point of fighting against the compromise of fifteen seats in parliament. Initially, he saw the 15 seats as a “tremendous achievement,” as did Nkomo.

This we rejected, and organised our own referendum, campaigning for a No vote against the 1961 Constitutional Proposals. Widespread civil disobedience ensued. We were critical of Joshua Nkomo’s leadership, on the grounds that he travelled too much and did not consult the Party.

Meanwhile, Robert Mugabe had returned to the country from Ghana. It was suggested that Mugabe be incorporated into the leadership, but there was a problem because he was not married. George Silundika and Moton Malianga approached a young lady called Abigail Kurangwa, who agreed to marry Mugabe, and eventually fell in love with him. Mugabe appeared to reciprocate, and his family liked Abigail, so all seemed to be proceeding smoothly. But in Ghana, Mugabe had had an affair with a Ghanaian woman named Sally. When Sally heard about Mugabe’s impending marriage to Abigail, she hastened to Southern Rhodesia and they were quickly married, while Abigail was sidelined.

Sally and I never became friends, and I never liked her. But I acknowledge that my ill feeling towards her was coloured by the way of poor Abigail had been used.

The NDP did not last long. We rejected the leadership of Joshua Nkomo, and tabled this at a Party Congress in Bulawayo in 1961. I was asked by the Salisbury District Council to table the motion. It was countered by none other than Mugabe, and this was the first of many confrontations between us.

Contrary to common perceptions, Robert Mugabe tended to defer to his leaders, right to the end. This was to happen again in the case of the sacking of Ndabaningi Sithole as leader of ZANU, whilst we were in detention at Kwekwe Prison in mid-1974.

We lost the motion in Bulawayo, and were under threat from Nkomo’s supporters. In the evening after the Congress, people with knives came looking for us, and we feared for our lives. It had been difficult even to leave the McDonald Hall where the Congress took place, but fortunately for us there were riots that night in Bulawayo, and we managed to slip away and go into hiding.

Some of the statements I made got me into further trouble. On a visit to a Tribal Trust Land (poor land reserved for blacks in Rhodesia), Mubaira Mhondoro, I stated that nothing would end colonial rule but outright war. This earned me an indefinite ban from the Tribal Trust Lands.

In the Salisbury Township of Mufakose, I earned myself another banning, by saying: “My father is a priest in a church. In this church are the people who came here with the Bible in one hand and guns in the other, and who vowed to use the guns if the Bible did not work. The only way is to fight them back with guns of steel!”

In December 1961, the NDP was banned. A week later, ZAPU (Zimbabwe African People’s Union) was formed. The formation of the new party took place thus: We sat in Nkomo’s house and discussed the new name for the party. We proposed the name ZANU (Zimbabwe African National Union), and Mugabe countered this with ZAPU, as he thought ZAPU had a better ring to it. The meeting agreed on ZANU, but at a press conference called to announce the new party, Mugabe unilaterally changed the name to ZAPU.

But there was no change of structure, merely a changing of letterhead. I continued my work as secretary of the Salisbury District Council. Early in 1962, my employer, Mobil Oil, transferred me to Bulawayo, where I worked for three months until I was moved again to Gweru.

In Gweru I met up with Kenneth Manyonda, a senior official at the African Trade Union Congress (ATUC), a breakaway from the union led by Reuben Jamela. In Harare, Nkomo was urging the leadership to go to Dar es Salaam and form a national government in exile. This made no sense to me, and neither did it to Julius Nyerere, but Nkomo lied to his colleagues that Nyerere had invited them to Tanzania to form a government in exile.

Sally Mugabe had a police case against her, and jumped bail. She and Robert Mugabe escaped through Botswana to Dar es Salaam. They were joined by the entire leadership. Nyerere told Nkomo to return to Rhodesia, which he eventually did, and immediately announced the banning of the anti-Nkomo group from the top leadership, led by Ndabaningi Sithole and including Mugabe and Enos Nkala. When the three arrived back from Tanzania, consultations began the formation of ZANU – The Zimbabwe African National Union. Thus it was that Nkomo was instrumental in the formation of ZANU – ironic indeed.

Ndabaningi Sithole had initially been a supporter of Nkomo, as he too, did not want to launch an armed insurrection. But after Nkomo’s action, he decided to join up with ZANU. Likewise, Mugabe would have remained with Nkomo were it not for his drastic decision to ban the top leadership of ZAPU. Besides, Nkomo had been a good leader in the early days when he worked with the Railway Workers’ Union and then as a social worker, and he had the ability to mobilise the workers.

Throughout the history of Zimbabwean nationalist politics, it has been a tradition that a person from a minority ethnic group is brought into the top leadership of the party in power. Ethnicity was a significant factor in Zimbabwean politics, which can be seen in the way I am always associated with Manicaland, where I happened by accident to be born, and yet I had spent my whole political life in Salisbury and Gweru. It was only later, after independence, that I came to be elected – in absentia – to represent Manicaland.

The formation of ZANU took a long time to organise – from October 1962 to August 1963. This was because we had to seek grassroots support at provincial level, and Salisbury District Council was often accused of behaving like the national leadership, of being the “troublemakers.” Right from the beginning, I was considered a radical. Amidst the discussions, it was formally announced in December 1962 that Nyasaland would be allowed to secede from the Federation. This decision was bitterly attacked by the Prime Minister of Southern Rhodesia, Roy Welensky.

On 8 August 1963, the formation of ZANU was formally announced – from Enos Nkala’s house in Highfield Township. The constitution of ZANU announced that Zimbabwe was, “An African country in the context of the African continent in various stages of the relentless process of overthrowing the yoke of colonialism, imperialism and settlerism.” Independent Zimbabwe, it said, had to have institutions that respected the will of the African people, who formed 96 percent of the population. ZANU resolved to confront the enemy by a “positive programme that can only result in bringing about equal opportunity and full citizenship to everyone, regardless of the colour of one’s skin, religion or sex.”

On the same day, Joshua Nkomo announced the formation of the People’s Caretaker Council (PCC), as a holding mechanism for ZAPU. There was a massive launching ceremony for the PCC at Cold Comfort Farm, Guy Clutton-Brock’s co-operative on the outskirts of Harare.

From Cold Comfort Farm, James Chikerema led crowds into Highfield, the township where allm the political activists lived in those days, and they attacked the houses of Robert Mugabe, Leopold Takawira, Enos Nkala, and beat up people on the streets. Highfield became a battleground.

Because of the fighting, we established a ZANU structure in Gweru. Rev Mawaro was chair, I was the vice chair, and Kenneth Manyonda was secretary. Joh Mutambu was in charge of Youth Affairs, William Takavarasha was the organising secretary, and Shangwa Muzenda was a member of the Council. Later, Rev Mawaro weas moved away from the area and I took over the position of chair. The Gweru District Council in fact served the whole Midlands Province, and even parts of Masvingo.

We agreed that we needed to be advised by mature minds, and so we created a council of elders who were to guide the elected executives, and rebuke us if we did wrong. (I am a firm believer in the idea of a Senate, and I had always advised Mugabe that he should create one). The council of elders included Mrs Chigwenere (mother of Ignatius Chigwendere), among others.

By temperament, I was more inclined towards the Youth Wing of the Party. The Youth Wing went to Masvingo to mobilise support for the Party in that town. In effect, we were fighting a war with ZAPU and, as ZANU was unable to operate in either Harare or Bulawayo, the Gweru structure was fighting for the whole Party. We would dispatch teams to the other cities, particularly at weekends, to fight battles. ZAPU would go into hiding when they heard we were coming.

I am very proud of the work I did in Gweru, for if it were not for I and my team in the Midlands, ZANU would have died then. Because of the situation in Harare, our first rally was held in Gweru, in Mutapa Hall, Mutapa Township, and it was a resounding success. Three times the capacity of the hall turned out, and the crowd gave heart to the national leadership.

Thus, it was natural that the Party Congress of 21-23 May 1964 should also take place in Gweru. Ndabaningi Sithole stayed at my house in Mkoba and campaigned vigorously to be elected President. Another group campaigned for Robert Mugabe, but Mugabe himself did not take part in the lobbying. The Congress duly elected Ndabaningi Sithole President, Leopold Takawira Vice President, Robert Mugabe Secretary General, Herbert Chitepo National Chairperson, and Edgar Tekere Deputy Secretary for Youth. For the first time, the Party reflected what we wanted to do – take over the government of the country. This had never been clearly articulated until that Congress. We also resolved not to rely on foreign troops. We would fight our own battles and, “no foreign blood shall be spilled on Zimbabwean soil in the process of liberating Zimbabwean soil.”

The Reverand Ndabaningi Sithole, President of ZANU, was a great teacher, who was able to use his abilities as a preacher to articulate the precepts of ZANU. It was he who first determined that ZANU should fight, openly confront the colonial power, and no other person could have done this better than he.

In accordance with this resolution, then, we had received orders to go on and form an army in the name of ZANU. Rev Sithole assumed an additional role -- that of Commander of the new armed forces. This decision was upheld by both the leadership and the delegates at the Congress. Now we had to find out how to form an army.

A Lifetime of Struggle by Edgar Tekere is published by Sapes Books in Harare. The book was edited by Ibbo Mandaza. Also in the series is The Story of My Life by Joshua Nkomo, also published by Sapes.

To order any of the books, E-mail: ibbo@sapes.org.zw or Call +263-4-252961/5 OR +263-4-704921, Fax: +263-4-252964

Newzimbabwe.com Serializes Cde E Tekere's Book!

The people who saved me from poverty

• Masawi threatened over Tekere book • Tekere unfazed by Zanu PF expulsion threats • Hysterical reaction to Tekere belies fear • Book shop won't sell Tekere book • Tekere absolves Mugabe of Tongogara's killing • 'We produced a creature that destroyed this country' - Nkala • Tekere says Mugabe 'insecure' in new book |

In his new book, A Lifetime of Struggle, Edgar Tekere delves into his controversial Life starting with his humble upbringing as the son of a Makoni Princess, his odssey into Mozambique at the side of Robert Mugabe, and his rise to prominence within the liberation movement of Zimbabwe.

Starting today, New Zimbabwe.com will exclusively publish extracts from the book which captures some of the most extra-ordinary events during the bush war that led to the country's independence:

Last updated: 02/26/2007 04:25:32

SOON after my return to Zimbabwe after independence, I made a statement in Parliament. My monthly income amounted to the princely sum of 0.38 cents. Yet I am an extremely wealthy man, rich in friends.

I have always had friends, but their true kindness came to the fore after I was sacked from the position of Secretary General of the Party. I did not confide the extent of my poverty to a soul, but they noticed, and quietly set about assisting me.

So here, I wish to name only some of them.

Roger Boka: I did not know Boka until, on my return to Zimbabwe after independence, he sought me out and introduced himself to me. He was interested, he said, in improving my image, so as to fit me for the new role I was assuming.

It was as if he had listened to Samora Machel give me one of his lectures prior to my leaving Mozambique. And fit (find?) me out he did. I was taken to an outfitter's and provided with three suits, several pairs of shoes, shirts, socks and ties.

When I was sacked from the Party, his concern mounted, and I would find that my rates had been paid, in credit. I would receive monthly cash payments, none amounting to less than Z$800,000.00, which was a goodly sum in those days.

I had not known how ill he was, when one day he arrived in Mutare in his new Rolls. He had come, he said, to see his old school at Old Mutare, and he wanted me to accompany him there. He told his driver to disembark, and instructed me to drive him to the school. He said to me, "You drive very embarrassing cars." (I was then driving a Mazda 323). "Let's see how you like the feel of a really good car."

He was to make presentations to the school, the church and the orphanage, and these he handed to me to give to the recipients. By the time we got back to Mutare, Boka was really very ill. I took him to doctor Kangwende, and later he went on to the governor, Kenneth Manyonda's home.

I did not see him again. Some time later, Tradex Marketing called to inform me that my new car was ready. What new car? I asked. The representative replied that they had been instructed by Roger Boka to have a Mitsubishi Twin Cab delivered to me forthwith. It was a 1997 model, fully paid for. This is the car that I drive to this day.

Baba Matongo: Baba Matongo owned a fleet of buses, and a supermarket in Mabvuku suburb, East of Harare. For a full eighteen months from the time of the Adams case he would drive to my house in Mandara and quietly drop there a stock of groceries. And I never caught him in the act. If I tried to contact him, he would always evade me, and when I finally did manage to thank him, he was not pleased at all!

Makomva: In 1983, Makomva arrived at my house in Mandara accompanied by the owner of Tanaka Power. We chatted a while, until it was time to leave, and I saw them to their car. Makomva quietly said to me that he had left an envelope in the lounge, telling me to read the contents later on. After they left, I opened the envelope, to find a cheque for Z$3,000.00. In 1983, this amounted to a small fortune.

Abdulatief Parker: Latief, as I called him, had settled in Harare from Cape Town. He was a businessman dealing in import/exports, and we had struck up a friendship sometime before. At one time Laatief opened an account in my name at a local bank, into which he deposited Z$500,000.00 every month for a period of three years.

After his return to Cape Town, he would send me air tickets, so that I could visit South Africa. During the course of these visits I became friends with the whole Parker family – Abu, a building contractor, Ali, a printer and staunch ANC supporter. Ali and another brother, Iqbal, took me to a Cape Town shop and bought me the finest pair of shoes I have ever owned.

I also developed a friendship with a Dr Elaine Clark, and I had regular medical check-ups at the hospital where she worked, the reports being passed on to Dr Pfumojena back home in Mutare.

John Williams: Through Latief, I met a number of South African academics, including John Williams. From 1991 he made regular payments to me of Z$6,000.00, during the course of an entire year. The three of us spent a lot of time together whenever I visited South Africa.

Jonathan Kadzura: Jonathan is a very successful businessman, and a close friend. After my sacking, he would often visit me at home, saying, "Ehe, mukoma Eddie, zvinhu zvenyu zvepolitics hino munodyei?" (Brother Eddie, you and your politics thing, what do you want with it?). This admonishment would always be accompanied by a gift of cash.